Currency Issuing Countries Versus Those With Full Monetary Sovereignty - What’s The Difference? Part 2

Concluding my examination of currency issuing governments in comparison with those with full monetary sovereignty.

In this article, I continue my discussion on the difference between countries that issue their own currency and those that can be described as having full monetary sovereignty. In part one, I provided simple definitions of these two phrases and gave examples of both the positives and negatives associated with said countries.

For technical reasons, the amount of material I could cover in part one was limited, which meant that it stopped abruptly. I’m starting this article just as abruptly. To get up to speed I recommend you read part one of this topic – click the link in paragraph above.

In part one I listed the advantages currency-issuing governments have over those who don’t. The former have:

The ability to fund domestic needs.

Control of tax policies: though often limited by circumstances.

Control over interest rates: though often limited by circumstances

Control of inflation: though often limited by circumstances.

Control over exchange rates: though often limited by circumstances.

I covered the first two points in my first article. In this article I conclude by covering points 3, 4 and 5.

3. Control Over Interest Rates, Though Often Limited by Circumstances

The central bank of a currency-issuing country sets the price of borrowing by establishing the base rate—the base rate is the rate at which commercial banks borrow from the central bank. This rate acts as a benchmark for general interest rates, including those for mortgages, business loans, and savings accounts.

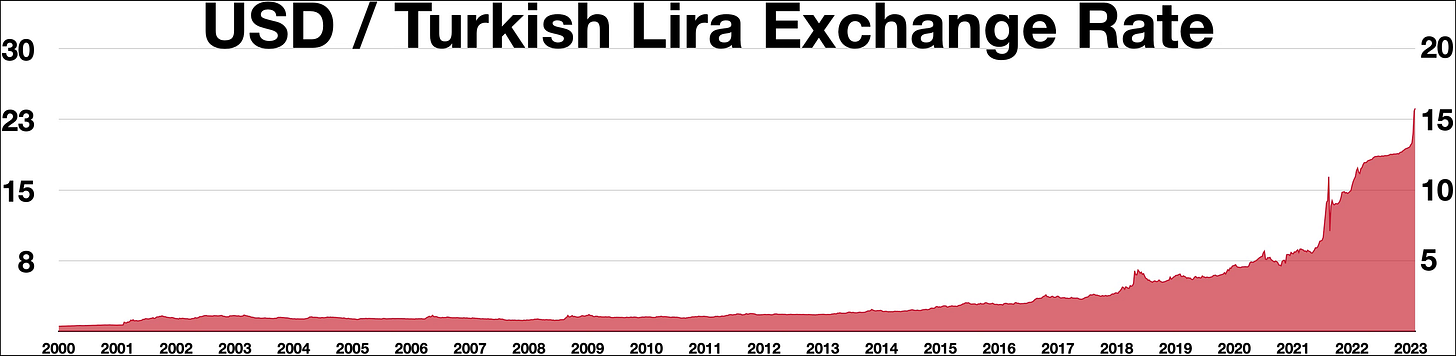

However, although central banks technically control interest rates, external pressures often influence that decision - often more so for countries that do not have full monetary sovereignty. As an example, let’s again look at the story behind Turkey’s interest rate changes since 2021. In 2021, the Turkish government, led by Erdoğan, cut interest rates several times as they aimed to follow the conventional view (i.e. orthodox economics) that lower interest rates stimulate economic growth. The idea is that as borrowing becomes cheaper businesses will take the opportunity to invest, and that investment will mean employing more workers—and those workers will spend their wages in the economy. This additional spending creates demand for even more goods and services. As a result the economy enters a "virtuous cycle" of economic growth.

However, the Turkish government had little time to find out if that was indeed the case. By 2023, with the lira depreciating, foreign debts increasing, and inflation rising, Turkey’s central bank reversed course and started to raise interest rates in an attempt to curb rising inflation

Summary of Turkey’s Inflation and Interest Rates

Inflation: In September 2023 inflation was 61.5%. By December it had risen to 64.8% (the Inflation Research Group estimated a real rate of 127.21%), and by March 2024 it peaked at 68.6%. By June 2024, inflation began to decline. At the time of this article the last recorded rate was 49.38% .

Interest Rates: In June 2023 Turkey’s central bank began raising interest rates and by October 2023 rates had reached 35%. In March 2024 interest rates peaked at 50% .

The Turkish government may well have wanted low interest rates but international investors, financial institutions, and policymakers put pressure on them to raise the rate. These actors believed that higher interest rates were needed to attract foreign investors—and that this would strengthen the lira—and would indirectly ease inflationary pressures.

The inflation that Turkey was experiencing was largely due to supply-side issues, i.e. driven by rising import costs and a weak lira, rather than demand-side issues. Demand-side issues are normally the technical reason used by orthodox economists to justify increasing interest rates, i.e. the argument goes that workers' wages get too high and cause the economy to overheat. Therefore, interest rates must be raised to increase unemployment (to tame the ‘overheating’ of the economy) which will reduce demand and bring down prices. A larger pool of workers to choose from implies that workers have less power to demand wage increases. Orthodox economists would point to the supply and demand curve for an explanation of why this is the case. When there is an oversupply of something the price of that something goes down.

Definition of the phrase, ‘demand side’: Demand-side refers to consumer and business demand for goods and services. This is assumed to influence economic growth, inflation, and employment levels. In the orthodox economists' inflation story, demand-side inflation is most often linked to workers demanding higher wages, which they can do because unemployment levels are low and workers are scarce. The idea is that wage increases equate to greater demand for goods and services, and this demand outpaces the supply of things to buy, pushing up prices and creating a "wage-price spiral". The wage-price spiral is where rising wages and prices continuously feed into each other, creating inflation. The conventional response to this scenario is to push up interest rates, which is assumed to dampen investment decisions and force workers out of work. The result is greater unemployment and workers with less spending power (because workers are no longer scarce), which halts the "wage-price spiral" and brings down inflation. A main aim of putting up interest rates is to increase unemployment in the economy.

Definition of the phrase, ‘supply side’: Supply-side refers to the production and availability of goods and services in an economy, shaped by factors like resources, labour, technology and access to imports. In countries without full monetary sovereignty—those reliant on foreign currency for essential imports and debt repayment—supply-side issues are particularly affected by external factors. For instance, geopolitical events like wars can disrupt global supply chains, driving up the prices of critical imports such as energy and food. This raises production costs domestically, fuels inflation and puts pressure on foreign currency reserves, especially for countries that rely on imports to meet basic needs and lack control over their own currency supply.

If you’re finding value in these articles, become a paid subscriber. Your support allows me to continue to write, teach and to build a community of like-minded individuals—individuals, like you, who understand that MMT offers an opportunity to change the world for the better. Become a paid subscriber now.

An MMT Perspective on Interest Rate Changes

MMT advocates argue that, contrary to the orthodox story, raising interest rates may actually increase prices rather than reduce them thus pushing up inflation. The logic being that high rates put more money into the hands of savers and investors, some of which gets spent into the economy, increasing demand. Additionally, as businesses face higher borrowing costs, they are just as likely to pass these expenses on to consumers through higher prices as they are to delay investment or lay workers off. Just as workers wages are a cost to business so is the price of borrowing.

Moreover, MMT suggests that high interest rates are ineffective (or less effective) when inflation is driven by supply-side issues. Turkey’s inflation, for example, was largely due to external factors: rising energy costs (influenced by the conflict in Ukraine); lira depreciation; and global food price increases. Turkey relies on imports for essentials like machinery, electronics and pharmaceuticals; the weaker lira raised costs across industries. Simultaneously, droughts affected Turkey’s agriculture, driving food prices higher. Clearly this does not fit the standard demand side story used to justify increasing interest rates in order to tackle inflation.

In economies with high levels of public debt (as in Turkey) or private debt, raising interest rates increases the cost of servicing that debt, which feeds inflation by raising business and consumer costs. Some studies in developing countries suggest that high rates can create a cycle of rising costs and reduced production capacity, further fueling inflation. See also: Inflation, rising interest rates, and developing economies.

MMT advocates say that interest rates are a blunt instrument; however, it is often the only instrument central banks have. Therefore, interest rates tend to be pushed up or down as the default response to inflation, whatever its causes.

Orthodox economists may or may not be correct in saying that raising interest rates will counteract demand-side inflationary pressures such as wage increases pushing up prices. However, in practice, it seems that the actual causes of inflation have tended to be ignored and there exists a default belief, that when there is inflation, interest rates must go up. As a result, the Turkish government felt pressure from international financial institutions, investors, and economists to reverse their interest rate policies; and the Central Bank raised interest rates.

I would also make the point that investors and savers tend to be the main winners when interest rates are high. It is in their interests to suggest that the government raise interest rates as a solution to economic ills, whatever their cause.

4. Control of Inflation: Though Often Limited by Circumstances

Much of what I’ve said above in relation to the control of interest rates relates to the tools governments use to control inflation. Therefore, in this section, I will try to stick to any additional issues that I have not previously addressed.

A country that issues its own currency but does not have full monetary sovereignty often needs to earn foreign currencies in order to pay debts and/or to import essential goods and services. For example, Turkey imports much of its energy and in the period of time we are discussing had to import food. Therefore, it was susceptible to exchange rate fluctuations. When the value of Turkey’s currency depreciated, imports and debt servicing became more expensive; and this put pressure on Turkey’s need to find ways to earn or borrow foreign currency.

Turkey’s situation was exacerbated by geopolitical events such as Russia's invasion of Ukraine that pushed up global oil and gas prices, as well as food prices—again making domestic goods and services that rely on these inputs more expensive.

The focus on acquiring foreign currency to pay for imports and to service debts takes the focus and resources away from serving the needs of citizens and from developing the domestic economy. That is, those resources are invested in increasing exports, developing the tourist sector, and/or other foreign currency-generating activities.

Turkey's focus diverted public resources from investments in social services, infrastructure, and the domestic economy, limiting the country’s ability to develop renewable energy sources and reduce its dependence on foreign fuel. As a result, Turkey faces recurring economic instability due to fluctuations in foreign currency availability and energy costs.

A MMT Perspective

MMT advocates would primarily point to the need to reduce dependency on imports of essential goods and services by investing in related domestic sectors as a step towards achieving full monetary sovereignty. For instance, Turkey could invest to become more self-sufficient in its agriculture and renewable energy sectors, thus reducing dependency on foreign food, oil, and gas imports. And relief measures could be used to help manage the cost-of-living impact on those with lower incomes. That is not to suggest that this is easy, as we saw with the development of Turkey’s defence sector.

As we can see, monetary sovereignty is not just about currency issuance; it is also about sovereignty in other areas of the economy, such as food, energy, and technology. It is harder to control inflation without full control of a country's core needs. Fluctuating exchange rates and geopolitical shocks have a greater impact on countries without full monetary sovereignty when those countries have structural weaknesses that mean they often have to earn foreign currency to pay down debts or to pay for imports related to everyday essentials like energy and food.

If you’re finding value in these articles, become a paid subscriber. Your support allows me to continue to write, teach and to build a community of like-minded individuals—individuals, like you, who understand that MMT offers an opportunity to change the world for the better. Become a paid subscriber now.

5. Limited Control Over Exchange Rates

“Nations with full monetary sovereignty—those that issue their own currencies, float their exchange rates, and don’t borrow in foreign currencies—can use fiscal policy to maintain full employment and price stability. A currency issuer with these powers is not financially constrained in the same way as a household or a business.” Bill Mitchell (Reclaiming the State, 2017)

As was saw when discussing the topics of interest rates and inflation, a country’s ability to maintain a stable exchange rate is an important policy aim. A stable exchange rate ensures trading cost are predictable, making it easier for both the government and private businesses to plan ahead. A stable exchange rate means:

The cost of paying foreign debts are more predictable.

There is a reduced risk for investors - which will attract more foreign investment .

It engenders economic stability.

It helps create confidence in the currency – which builds trust with businesses and consumers.

In short, a stable exchange rate and predictable costs help both the private sector and the government with long-term planning. I have demonstrated in the previous sections of this article how difficult exchange rate management can be, even for countries that issue their own currency, when they have structural weaknesses in their economy.

Turkey has mainly tried to manage its exchange rate through interest rate adjustments, the use of foreign exchange reserves and capital controls. It has also promoted exports and tourism to bring in foreign currency and occasionally intervened directly in the currency market to stabilise the lira.

Defining Capital Controls: Capital controls means placing restrictions on the flow of foreign currency in and out of a country in order to limit speculative attacks. Those restrictions could include limits on foreign currency holdings or restrictions on repatriating profits. The downside to capital controls is that they can deter foreign investors and that could impact long-term investment inflows.

One way to achieve a stable currency is to peg its value to another currency (like the US dollar) or a commodity (like gold). However, if the peg breaks or the country runs out of reserves, its currency could lose value quickly, creating economic instability and making imports more expensive, which feeds domestic inflation. Turkey has not officially pegged its currency to another country's currency or to a commodity like gold; however, it has at times implemented a managed float system, where the Central Bank intervenes to influence the lira's value in relation to foreign currencies. For further information on this topic, see the article, Turkish Lira: From peg to managed float?

Currency Issuance Is Required, but It Is Not Sufficient for Full Monetary Sovereignty and It Is Not Sufficient for Full Economic Sovereignty

Although this article is about the differences between currency issuing governments and governments with full monetary sovereignty, what it also reveals is that monetary sovereignty in itself is not enough for full economic sovereignty if a country does not also have food and energy sovereignty - or other essential inputs to the country’s economy. When a country needs to import essentials, that implies a need to find foreign currency to pay for those essentials. That either means earning foreign currency or borrowing foreign currency.

For countries without full monetary sovereignty, such as those that peg their currency or rely on foreign currency reserves, this reliance makes them especially vulnerable to external pressures as they must maintain access to foreign currency for vital imports.

Currency issuance is a critical component of full monetary sovereignty but it is not the whole story. Full monetary sovereignty also requires.

Avoiding significant levels of foreign debt.

Domestic access to critical resources such as food, energy and technology.

Maintaining an educated workforce to make use of those resources.

A balance of payments that does not create ongoing foreign currency dependencies—i.e. the country can meet its external obligations through earnings without resorting to borrowing or draining reserves.

A structurally sound, diverse economy that can withstand unexpected shocks.

An economy dependent on importing critical resources will always face the challenge of securing foreign currency to pay for those imports. This dependence can lead to government policies that prioritise managing foreign debt over improving the wellbeing of its citizens. Ultimately, true monetary sovereignty requires an economy resilient enough that it can prioritise domestic prosperity without being constrained by foreign currency needs.

An MMT Perspective

There are no simple solutions for countries such as Turkey that issue their own currency but do not have full monetary sovereignty. As I discussed earlier, MMT advocates would say that countries should seek to address the structure weaknesses in their economies: i.e. weaknesses that mean they currently have to import core essentials such as food and energy. However, when I looked at the example of Turkey developing its own defence sector, earlier in this article, that meant it had to import the machinery required to develop that industry: and that need caused further problems for the economy. Addressing structural weaknesses is the aim (as the country works towards full sovereignty), it is not something that can be fixed overnight as the process itself can be disruptive and lead to the very issue that the policy is designed to address.

A Discussion of What It Means to Have Full Monetary Sovereignty

“A government that issues its own currency has much greater fiscal capacity than one that borrows in a foreign currency. With full monetary sovereignty, a country can never run out of money. It can always pay its bills, support public services, and manage unemployment—so long as inflation remains under control.” Stephanie Kelton (The Deficit Myth, 2020)

In part three, I will discuss the advantages that countries with full monetary sovereignty have over those that just issue their own currency. As a reminder, here is what I said were the requirement to say that a country has full monetary sovereignty:

To have full monetary sovereignty the following conditions must be met:

The government issues its own currency.

The government does not borrow in foreign currencies and, therefore, has little or no foreign currency debt.

The currency’s value is not pegged to another currency or commodity (i.e. the exchange rate floats).

The government—via the central bank—has full control over interest rates.

The government can spend as needed to meet domestic priorities as long as inflation is under control.

As you can see, I have already discussed many of these issues as they relate to countries that issue their own currency: countries that have not yet achieved full monetary sovereignty. Although MMT uses the phrase full monetary sovereignty a more accurate phrase might be full economic sovereignty - as the phrase full monetary sovereignty implies much more than sovereignty over a country’s currency.

Do you agree? Do you disagree? I welcome your comments either way. Please comment below.

If you’re finding value in these articles, become a paid subscriber. Your support allows me to continue to write, teach and to build a community of like-minded individuals—individuals, like you, who understand that MMT offers an opportunity to change the world for the better. Become a paid subscriber now.

Jim Byrne - MM101.ORG

Resources

Links to some of my most popular newsletters

Become a paid subscribers for access to additional content:

A Permanent Home for MMT101 Paid Subscriber Resources – Factsheets, book recommendations, academic papers, MMT podcasts and more.

MMT Factsheet 3: If Taxes Are Not For Spending What Are They For?

Support MMT101.org by Becoming a Paid Subscriber

If you are enjoying these articles and find them a useful part of your Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) education, please support MMT101.ORG—if you can—via small donation. $5 (or the equivalent in your own currency—SubStack uses US dollars) will allow me to continue this work and reach & teach more people. If you can’t do that, consider sharing the articles and podcasts. By subscribing and supporting, not only will you learn how the economy works, but you will also be part of the efforts to change people’s lives for the better. I do not have the power to do that alone, but as an ever-expanding group who understand that there is a better way, we can make a difference.

Thanks,

Jim

Subscribe now to learn how we can make the economy work for citizens and the planet.