Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) in 70 Bullet Points

This is a working document. It was last updated on July 13th 2025. I intend to continue editing and adding to each of these bullet points over time.

I’ve been regularly updating this post since I wrote it one year ago (14th July 2024). In fact, I updated it again only a couple of days ago with information about why Warren Mosler is not a fan of MMTers using the phrase “taxes don’t fund government spending”. You will find that update as a sub-section of bullet-point 42.

Tomorrow is the anniversary of its original publication, so this feels like a good time to send you the updated version. It has been, and continues to be, my most popular post. I guess I must have captured something — or maybe it’s because it covers so much ground that it’s a useful summary of MMT as a discipline? I don’t know. Post your thoughts in the comments section below. And if you are not already a subscriber, please subscribe.

MY MMT Online Training Course Is Now Live!

One more thing. I’ve just published my first MMT online training course called MMT101 – The Why, The What and The How of Modern Monetary Theory – check it out. Note that it’s free for paid subscribers, and for all subscribers there is a 70% discount. If you missed my email about it, just get in touch and I’ll send you the discount codes. Thanks for your continued support. Have a great day.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) describes and explains how the monetary system works and how governments can use that understanding to manage the economy.

1.1.Defining of the phrase, ‘the monetary system”. The monetary system is the system that governs how money operates within an economy. How it is created, circulated, and used to buy and sell goods and services. It describes the types of currency in use, i.e., digital forms or physical coins and banknotes. It outlines the rules and institutions governing their value and the exchange rates with other currencies.

MMT descriptions and explanations are primarily derived from observation and historical analysis, rather than theoretical models. MMT seeks to find out and examine where money comes from; the institutions it flows through; and the role it plays in society and the economy.

Having said that, MMT economist Bill Mitchell points out that MMT does indeed have a theoretical aspect: because our observations tell us how things work in practice, which gives us insights into 'what causes what'. This allows us to design smarter policies and to predict the outcomes of those policies. So, MMT is not just about understanding the mechanics of the monetary system—it provides a framework for analysing that system.

“I think it is without doubt that economists who see the world through an MMT lens have been much more successful in making statements about future events, particularly following major policy interventions, than our mainstream colleagues.” Bill Mitchell – Understanding what the T in MMT involves

The story of how and why money was ‘invented’ is important, so I will start with a brief exposition on that point. It’s important, because it can either be used to support the approach taken by orthodox economists (Adam Smith Wealth of Nations Chapter IV, Carl Menger – "On the Origins of Money" (1892), Paul Samuelson – "Economics" (1948)), or it can be used to support the approach taken by MMT advocates. The former say that money arose spontaneously to ‘lubricate markets, via barter, and therefore it belongs to the people operating within those markets’. The latter that it originally arose from social networks and keeping records of debts and obligations within communities. These records and associated legal framework were kept by central authorities, such as local religious temples and latterly, national governments.

If you have any questions or if you disagree with anything I write in this article, I want to hear from you. Please add your comments in the discussion area. Contrary views are welcome.

If, as an orthodox economist, you can develop a story that shows ‘money came from the people’, you can argue that the governments role in managing that economy is not wholly legitimate. You also feel justified in saying that the government is interfering with the workings of the market, preventing it from doing its job as well as it could. I.e, it’s best not to interfere with individuals pursuing their self-interest, in a free market, because that’s the best way to ensure positive outcomes for all concerned.

The orthodox approach says that government spending reduces the availability of goods, services and money that would otherwise be available for private sector use. Develop that further and you can justifiably say that the government stole the people’s money and spent it wastefully. This story supports the idea that governments should not have a large role in the working of the private sector economy.

Note that MMT economists dispute this assertion, i.e., that government spending reduces the availability of goods, services and money that would otherwise be available for private sector use. However, that debate is for another time.

It’s no surprise, therefore, that orthodox economics textbooks to this day still tell us that money arose from barter systems. (Reference: Graeber; Stevenson and Wolfers) Moreover, many of the mathematical models used, still treat markets as if they were barter systems.

What do I mean by a barter system? In a barter system if you are a carpenter, and need food for your family, you exchange a chair or some other wooden piece you’ve made, for food from the farmer (or indeed anyone who specialises in growing/making food). If you are a blacksmith and want a musical instrument, you give the instrument-maker a hammer, a poker and a spade, and he’ll give you a guitar. Of course, if you think about this for more than a few minutes you start to realise that you have no future as a guitar player. Sorry, what I meant to say was; you will realise there are flaws in this system.

If you want food but the farmer doesn’t want wooden furniture or you want a guitar but there aren’t any guitar makers to trade with, that’s a problem. Think about it for a few minutes more and you might realise that in every transaction - both parties must have the goods or services that the other wants. This is called the ‘double coincidence of wants’ problem. A few more minutes and you’ll start worrying about how the boat building knows how many chickens his boat is worth - and where to find the man or woman with all the chickens. And now you are thinking about how the cobbler can divide up his boots when he only wants one apple from the orchard. That’s called, the indivisibility problem. It’s getting complicated.

Orthodox economics tells us that money evolved naturally as the answer to these barter system flaws. You just need to figure out how much everything is worth (that’s called, the need for a common measure of value) and you can exchange the shirt you made for a certain number of coins, then you can buy the lettuce from the market gardener. The market gardener can accept your money, save it along with all the money he/she has made from other transactions and buy that boat. And now the boat builder can buy his chickens. And finally; you can buy that guitar you’ve always wanted.

While I have your attention, did you know I have a comprehensive MMT online training course that is free for paid subscribers?

The classical economics story is that money originated from people bartering goods and services; an early form of our modern capitalist marketplace. So, money came ‘from the people’ to support their market activities, not from the government. This story helps downplay the role of government in the management of the money system. It promotes the idea that money was ‘stolen from the people’ by a central authority by nefarious means. And that governments should leave markets alone to get on with what they are good at.

People have always used barter, and still do, that is true. However, there’s no evidence than societies ever used barter as a general market system. Or that money spontaneously developed from it. So, if you are the sort of person who prefers evidence based stories (rather than intuition), I suggest you read David Graeber book, ‘Debt: The First 5000 Years’. It explores the historical and anthropological origins and implications of debt and money systems. He presents evidence that suggests money appeared out of social and moral obligations within communities. It was related to the creation and canceling of debts within communities. It was not simply an economic transaction, it was a social and moral construct. Graeber’s text does not find evidence to support the idea that money arose from the barter system.

Unlike neoliberal economics, MMT puts forward the idea that governments were central to the creation of our modern monetary system. So, rather than pushing governments aside, as an impediment to the market working as it should, MMT reveals its central role.

MMT studies the governments role in the monetary system. It studies the processes through which government money is created; it studies how the central banks interacts with commercial banks; and it studies how money flows between government sector, non-government sector and foreign sector.

As I said earlier, although there is a theoretical aspect to MMT, when compared to orthodox economics, it is more about observation rather than theoretical models and frameworks. It looks at the mechancs of the monetary system as it seeks to answers questions such as, “Why did monetary systems come into existence?”, “where does the money that the governments spends come from?”, “why does a government that issues it’s own currency need to borrow?”, “what is actually happening when interests rates are pushed up by the central bank?” “What caused the inflation after the Covid pandemic?”. MMT tries to answer questions by studying the observable facts and the flows of money within and between different sectors of the economy.

MMT also aims to learn from the past. MMT looks at past economic data and evaluates and contrasts the outcomes from different approaches and policy decisions. For example, MMT advocates will contrast whether policies based on taxing and spending (fiscal policies) provides better outcomes than policies based lowering and raising interest rates (monetary policies). Outcomes are measured in relation to their impact on employment, inflation, GDP, business growth, the business cycle, trade deficits, exchange rates and other measurable real-world outcomes.

MMT does not study these topics through the traditional lens of classical economics or adopt orthodox economic assumptions and theoretical frameworks. i.e., assumptions such as; individuals make rational decisions based on their own self interest; if left to its own devices the market it will tend towards equilibrium; small government is good, large government is bad; lower wages mean more people get employed; the level of employment and the level of inflation are linked, and so on. These assumptions are neither self-evident nor free from an ideological bias. One of the first things I thought when I was presented with the assumption of the self-interested, rational individual who believes that they alone are responsible for their own successes or failures was that this sounded like an individual with a political viewpoint. One that most of us could quite easily identify.

MMT tells us that money is not just a tool to enable markets; it's a complex social institution with historical, cultural, and societal significance. Money affects people's lives, their behaviours, and the overall functioning of society. Money is a product of human behaviour and shapes human behaviour. Money influences the quality of life for citizens and the overall well-being of communities.

MMT goes beyond asking questions and describing what it finds. It suggests that if you understand how the economy actually works that understanding can be used to solve real world problems. It allows us to ask and answer questions such as, “what economic conditions and policies allow us to provide a job for everyone who wants one”, “how can we afford to accelerate the move to renewable energy sources’, “what does a country with unused productive resources, but little spending power, have to do to utilise those resources?”

As economists Bill Mitchell pointed out earlier, MMT provides a framework for exploring these and other real issues. Stephanie Kelton, the author of ‘The Deficit Myth’ tells us, that governments should not aim to balance the books; rather it should aim to balance the economy. By this she means that government policies should be about promoting economic stability and the wellbeing of the our citizens, rather than trying to balanced the budget for its own sake. An MMT advocate would say, “currency sovereign governments should be measuring outcomes, such as how well the countries resources are being put to use - and to do things like invest in renewable energy and build a wellbeing economy - and not so much time worrying about the size of the deficit”

A definition of the world ‘deficit’. A deficit is when a country spends more than it brings in in taxes and other revenue. Spending including interest paid out on government bonds.

What is a government bond? Think back to a time when government bonds and money were always physical pieces of paper. Visualise a bond as being the same as paper money, but the holder of the bond gets interest paid on and the holder of money doesn’t.

MMT believes that the orthodox understanding of how the monetary system works is incorrect and deprives governments of the tools needed to manage the economy. MMT presents a new way to think about the monetary system that provides insights into how to both understand the economy and how to use that understanding to solve problems.

Central to the MMT approach is a recognition of the difference between currency issuing governments and currency using governments. Currency issuing governments are governments that spend their own currency into existence. The UK, for example, is a currency issuing government. Currency using governments are governments that have to find currency before they can spend it. Scotland is a currency using government. It uses the UK pound. Being a user of the UK pound places restrictions on what the Scottish Government can do. For example, the Scottish Government was not able to go into lockdown during the Covid pandemic until the UK Government released the funds to support Scottish businesses. The Scottish Government wished to lockdown a number of weeks before the UK Government - but was unable to - because it was not a currency issuer, it was a currency user.

Note, that paid subscribers resources are now on this page. Downloadable factsheets, a downloadable dictionary of economic jargon, my book/journal recommendations and more.

Much of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) focuses on the differences between currency-issuing and currency-using governments, particularly regarding their ability to implement policies and influence economic outcomes. For example, a progressive government might aim to develop a wellbeing economy, whereas a right-wing government might aim to strengthen border enforcement. MMT examines whether such a policy, or for that matter, any policy, is financially feasible.

What is affordable or not affordable can be related to how much freedom (i.e., how much ‘monetary sovereignty’) a government has to manage the economy via government spending. Government spending and taxation is called fiscal policy, which is about spending and taxation as opposed to monetary policy which is about raising or lowering interest rates.

MMT views financial transactions between different institutions and sectors from the perspective of an accountant, using double-entry bookkeeping. As economist Steven Hail writes, MMT views the economy as just a big set of ‘interlocking balance sheets’.

Double-entry bookkeeping is an accounting system in which every transaction is recorded in at least two accounts, both the debits and credits are recorded. Total debits must always equal total credits for each transaction.

Professor Steve Keen writes, “Modern Monetary Theory is accounting… because what money is is a creature of double-entry bookkeeping. This was invented back in the 1500s in Italy. So you want to keep track of your financial flows, then you divide all the financial claims on you. You divide into the claims you have on somebody else which are your assets, and claims someone has on you, which are your liabilities and the gap between the two is your equity. So you record every transaction twice on one row.”

So, MMT, recognises that there are two sides to every transaction. A government sector deficit implies a non-government surplus. It is axiomatic to say: in any given period, the amount of money spent by the government sector equals the amount of additional money added to the non-government sector.

For example, if I give you five pounds, I’ve got five pound less, you’ve got five pound more: me being £5 pound down is mirrored by you being £5 up. Similarly when the UK Government recorded a deficit of £300 billion (in nominal terms) in the fiscal year 2020-2021 (Office for National Statistics (ONS)) - that’s a £300 billion (in nominal terms) surplus in the non-government sector. The deficit and the surplus mirror each other.

This example shows the absurdity, for currency sovereign governments, of the phrase, ‘the country is in debt and your children will be paying for it for years to come’. The government and the private sector are in the same country. The government spending money into the private sector does not push the country into debt. It is a liability to the government but that liability is mirrored by additional financial assets in the private sector. When you are the source of all currency for a country, money spent today does not restrict spending in the future - and does not create a ‘debt’ as we normally understand the word.

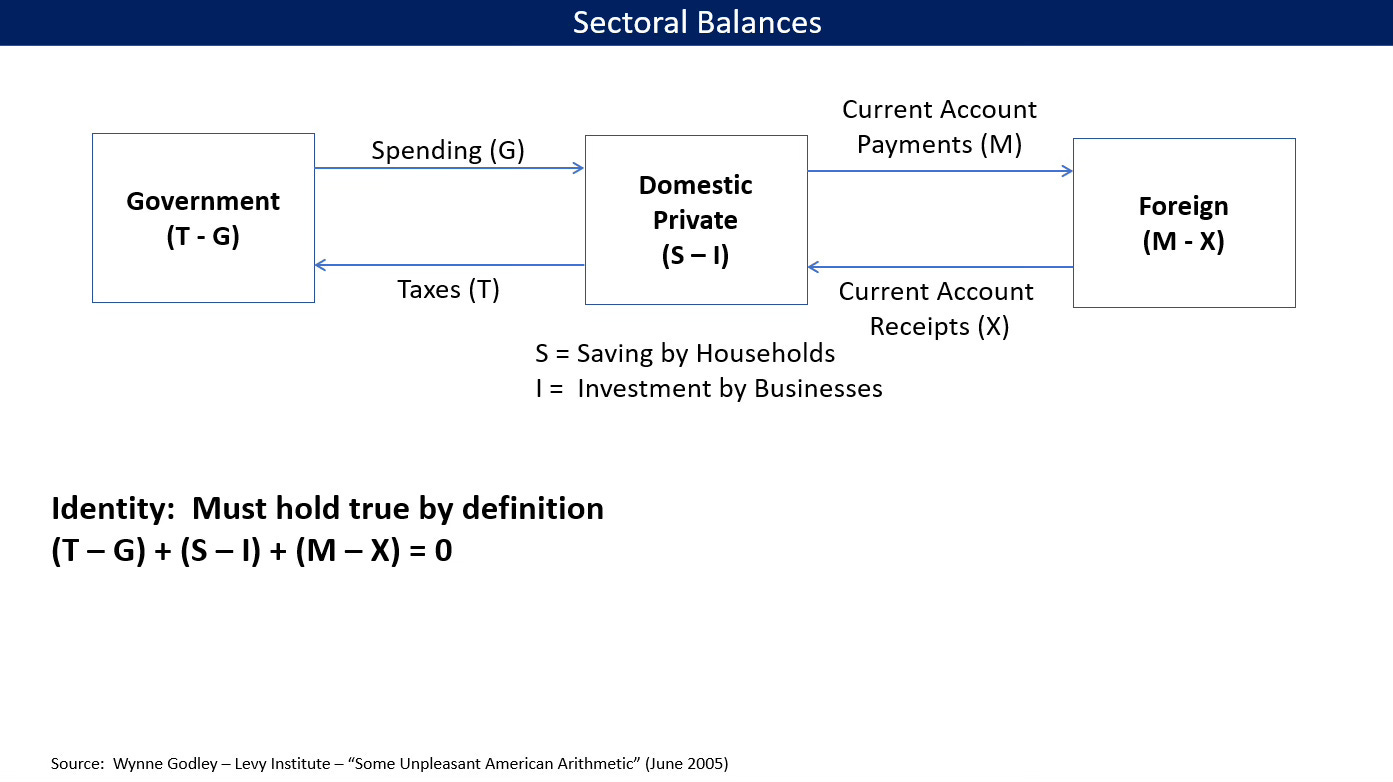

If the UK Government spends money spent into the private sector and does not take it all back in the form of taxes - that tells us that some of that spending remains within the private sector. For example, if the government spends £100 and taxes back £90, £10 remains in the private sector. £10 is added to the government deficit. If the government spends £100 into the private sector and taxes back £110 in taxes, £10 has been removed from of the private sector. That extra £10 the government now has is recorded as a government surplus. However, the private sector now has less money to spend/invest - £10 less. Stephanie Kelton in "The Deficit Myth" references the work of economist Wynne Godley to expand upon this point. Godley used the 'stock-flow consistency model' to demonstrate that financial balances must sum to zero across all sectors of the economy. A deficit in one sector (such as the government sector) must correspond to a surplus in another sector (such as the private sector or the foreign sector).

A definition of the phrase 'Stock-flow consistent (SFC) modeling': SFC is an approach in macroeconomic analysis that ensures all financial transactions and their effects on stocks and flows are consistently and accurately accounted for across all sectors of the economy.

Definition of the words 'stocks' and 'flows' in relation to economics. 'Stocks' refer to the amount of assets or liabilities held at a particular point in time, while 'flows' represent the changes in these quantities over a specific period. An example of stocks would be the amount of money in your bank account at the end of a particular year. The 'flows' would be the deposits and withdrawals you made during that year.

If you’re finding value in these articles, become a paid subscriber now. You will help me to continue to write and teach on the subject of MMT.

MMT asks us to think of the money in our economy like the blood that flows through our own bodies. Without it, nothing works. Draining the blood out of our body kills us. Draining money out of the economy risks killing the economy. For example, by running surpluses, (a surplus means taking more out in taxes than is spent) is likely to push the economy into a recession, if that surplus is not balanced by some other sector running a deficit. That other sector could be, the foreign sector. The private sector has a propensity to save for a rainy day. When things start to get tight, their spending stops and the economy contracts.

Neoliberal economists focus on their desire to reduce the role of the government. This means they wish to keep government spending low - which in turn means they want avoid large governments deficits. Rather, they want to bring down government ‘debts’. Bringing down government debt is the idea behind austerity policies. However, evidence shows that the results of austerity is actually larger deficits - as people have less money to spend, businesses contract - and overall the government receives less in taxes. The end point is a larger difference between the amount taken in taxes and the amount spent in government, i.e., a larger deficit. The phrase ‘running a government surplus’ means the same as the phrase ‘removing money from the private sector’. You are in the private sector, you now have less money to spend.

MMT recognises that austerity makes the economy weaker, lowers growth rates and increases the government deficit. It also erodes services and drives millions of people in lower income brackets into poverty. In 2017 the British medical journal estimated that 120,000 lives were lost due to policies austerity. In 2023 The Guardian estimated that figure to be closer to 330,000.

If I was the source of all UK pounds, when I give you a five pound note, I can also give you another one at any time, without having to wait for you to gave back the original one. However, according to neoliberal economic orthodox , I do indeed have to wait, because they are worried that if I loan you another fiver my debts are increasing and that’s dangerous for my future because it will be harder and harder to pay that off. But I make the five pound notes - so how is that really a debt? Logic tells us that it can never be harder for me to give you another fiver in the future - when I can always make more five pound notes.

Tax revenues do not pay for government spending. “This idea that you run government like you run a household and you actually have to earn tax revenue to even be able to spend and otherwise you have to, you know, do austerity, is a complete myth. Governments create money all the time. I mean, look what happened in Germany recently overnight. They created 100b Euros for the war effort. So, why do we actually treat our social around health, around public education, public transport, climate change as urgently as we treat climate. And then use tax to redistribute in a progressive way, not a regressive way and to steer the economy to be more inclusive and sustainable. ” Prof Mariana Mazzucato - Professor in the Economics of Innovation and Public Value at University College London - on BBC Newsnight:

Tax revenues do not pay for government spending. "The government doesn't need your tax dollars to spend. It creates the money it needs whenever it spends. Taxes serve other purposes like controlling inflation and redistributing wealth.” "Governments that issue their own currency are not financially constrained in the same way as households or businesses. They can always afford to buy anything for sale in their own currency, including paying people to do useful work. Stephanie Kelton - Author of The Deficit Myth and professor of economics and public policy at Stony Brook University. Stephanie served as an advisor to Bernie Sanders's 2016 presidential campaign and worked for the Senate Budget Committee.

Tax revenues do not pay for government spending. "Sovereign currency-issuing governments like the United States are not like households or businesses. They can never run out of their own currency, and they can afford anything for sale in their own currency.” Pavlina R. Tcherneva - Associate professor of economics at Bard College. An American economist, of Bulgarian descent.

Tax revenues do not pay for government spending. "We've been conditioned to think of the government's budget like a household budget, but it's not the same. Governments that issue their own currency operate on an entirely different financial basis.” Stephanie Kelton

Tax revenues do not pay for government spending. "Taxes are not the primary source of revenue for currency-issuing governments. They have the ability to spend by creating money ex nihilo.” Gail Tverberg - Author of Our Finite World

Tax revenues do not pay for government spending. “I have not been worried about the state deficit for sometime, ever since Mr Brown found out that the UK state can literally print money to pay its bills.” John Redwood, Conservative MP for Wokingham

Tax revenues do not pay for government spending. “…Rishi Sunak is entirely right to borrow mind-blowing amounts of money because the essential task is to keep the economy going. Fiscal hawks will say that this all our money and it has to be paid back. Well no, it is not actually all our money. A lot of it is the Government’s money, which they generate from the printing presses of the Bank of England.” Lord Horam (originally a Labour MP, defected to SDP, now a Tory)

Tax revenues do not pay for government spending. “When the fed wants to pay money to a bank it’s not tax money, we simply use the computer to mark up the account” Ben Bernanki, Former chair of the US federal reserve

Tax revenues do not pay for government spending."The money government spends doesn’t come from anywhere, and it doesn’t cost anything to produce.” Economist James K. Galbraith referring to currency sovereign governments.

Note that Warren Mosler, the ‘father of MMT’, is not keen on the phrase “taxes don’t fund spending”. He points out that when governments first introduced taxes, they did it as a tactic to resource themselves. I.e., to recruit citizens for their army, workers for their health service, and resources for their infrastructure projects and so on. One way to get those resources was to enforce a tax on citizens: a tax that must be paid in the government's own currency. The tax was legally enforced. That is, if citizens don’t pay their taxes, they go to jail. So, in a roundabout way, taxes do indeed fund government spending. The taxation system enables the government to get the services and things it needs: because it forces people to work to obtain the government's currency. They either need to work directly for the government or for the non-government sector. This is why I hedge my bets by saying that “tax revenues don’t fund spending”—and not “taxes don’t fund spending”.

However, having said that, in practice, all government spending is new money. Spending decisions first spring from the minds of politicians (even non-discretionary spending like pensions and public sector wages)—which are then ratified by governments/parliaments. The central bank then implements those spending decisions (via instructions from the Treasury) by depositing money into the reserve accounts of commercial banks. Reserve accounts are the accounts that commercial banks have at the central bank. The commercial banks then mark up the accounts of those receiving the money for whatever services or goods are being bought.

There is never a need to check to see if there’s any money left in the coffers, because there are no coffers; money does not exist until it is spent (and just as an aside tax legislation and spending legislation are not linked). All spending decisions made by the government must legally be carried out by the central bank—so it’s logically impossible to say that ‘there is no money left’. There never was a finite pile of money for the government to draw upon: the UK Parliament decides to make a payment, that payment is made; the process of making that payment is to type figures into a computer. It is only at that point that money comes into existence (as in, money that can be spent on goods and services).

So, although Warren is correct to say that it all started with the imposition of taxes, once the process is up and running, it is not tax revenues that, in practice, pay for things—there is no pile of tax revenues. However, like a ball rolling down a never-ending slope—once you give it that initial push—it will roll forever. Similarly, there is no end to the number of spending decisions that politicians/governments can make. But there does come a point when there are no longer things that can be bought by that money, because stuff for sale in the government’s currency will eventually run out. In short, stuff is finite, even though government money is not.

Ok, that was a little diversion to introduce Warren’s point about why he thinks MMTers should not say that ‘taxes don’t fund government spending’. My next point is a simple one: the money you use to pay your taxes is drawn from the pool of money the UK government previously spent into the non-government sector. Why? Well, because the government is the only source of net new UK pounds. And no (I’m ‘heading you off at the pass’ here), it wasn’t the commercial banking sector that created the money—despite bank money making up most of the ‘money supply’. Bank loans are repaid, and the repayment cancels the loan. Unlike the government, banks don’t create net new money—they create loans. So, when you pay your taxes, you are just giving some of the money the government spent back —as a way to cancel your tax liability.

If we were to define the word ‘debt’ in the same way an individual or business would define it (i.e., the possibility of bankruptcy and financial stress), we would have to say that currency-issuing governments cannot go into debt in their own currency (though they can in a foreign currency). As we found out earlier, when a currency-issuing government spends, they create money from nothing other than the instruction from politicians in government. Unlike individuals and businesses, there is never a ‘debt’ that the government cannot pay, as long as it is in the currency they themselves issue.

It is true to say that an accounting liability is created on the government’s ledger. But, again, this liability is like no other, because no matter how big it is or becomes, it does not effect future spending decisions. There are other things (for example, inflation) that will affect future spending, but the size of the government's liability, or debt if you still insist in calling it that, is not one of them.

Accountants will know that when there is a liability, there must be a corresponding asset: the asset is the money that was spent into the non-government sector. If you added the liability and the assets together they would balance to zero. That is why, even if you wanted to use the word debt, it is never true to say that the ‘nation is in debt’ when you mean the government. The asset side of that equation is the money that was spent into the non-government sector: i.e., the money that created that liability.

The limits to government spending for currency issuing governments - are not financial – they are the real resources available to buy/use. When those become scarce prices are pushed up - which can cause inflation. Those real resources include: people, the factories that make things, energy, capital, knowledge, skills, raw materials, time, and of course the ability of the natural environment to absorb and manage waste and pollution.

It is no just government spending that potentially pushes up prices (I will ignore supply-side causes for now) it is the combination of government and non-government spending. Which brings us to another useful reason that the government to collect taxes: it decrease that spending power of the non-government sector - leaving room for more government spending. A country needs a healthy, educated population, a civil service, a defence force, roads, food, energy, water and more. However, if the combined spending of the government and the private sector is driving up prices - the government can take money out of private bank accounts via taxes, and/or by selling bonds. Less money in bank accounts means reduced private sector spending, leaving space for more government spending.

As I’m sure I’ve mentioned often, observation and descriptions are at the core of the MMT approach, however, there is also a theoretical aspect. When an MMT economist goes from observing the mechanics of the economy to predicting the result of a government policy - that requires a jump from ‘the what’ to ‘the why’. And that requires theoretical conjecture. However, unlike orthodox economics, MMT does not first come up with a theory, build a model based on that theory and then use that model to generate the expected outcomes. Instead MMT starts by observing the real economy: the real institutions, the real mechanisms at work - then makes predictions based on what it sees. Famously, MMT advocates illustrate this in the following way: by saying that orthodox economists try to understand and predict the behaviour of horses by thinking about horses. MMT proponents study real horses, take notes and make pronouncements based on what they have found.

Unlike classical and neoliberal approaches that deify the private sector and say that the governments role should be minimised, MMT, as mentioned earlier, recognises the government plays a central role in the economy. MMT recognises that the currency the private sector uses to do business and to generate wealth comes from a central authority. That central authority provides the currency, the legal frameworks and the public works and institutions (e.g., roads, bridges, education, and infrastructure) that allow markets to operate. There are no markets, there is no private sector without a central authority to organise the context within which those markets can operate. We call that central authority ‘the government'.

For currency issuing governments it is not finances that constrain economic actions. It is real resources. Those real resources are ultimately constrained by the limits of our planet. So, there are limits to what can be consumed, limits to what can be produced. However, for governments with full currency sovereignty there are no financial limits; they can never run out of their own currency.

If taxes are not used to fund government spending what are they for?

* Taxes enforce the use of the national currency - making it the legal tender. In the UK that is the pound. That is the only currency you are allowed to pay your taxes in. ‘Anyone can print money - but the trick is to have it accepted’ - a quote often attribute to Warren Mosler the founding father of MMT. That’s easier when it’s against the law to pay your taxes in anything else. We all use the pound and we all agree that goods and service for it and be paid in it.

* Taxes can be used to redistribute wealth, i.e., a progressive tax system. Take a larger proportion from the wealth and a smaller proportion for the less wealth. This is also good for the economy - because the wealth save their money and those with less tend to spend it.

* Taxes can be used to encourage some behaviours and discourage others. For example, you could reduce taxes to to firms who buy electric cars rather than petrol cars for their fleets.

* Taxes take money out of the economy - to allow the government room for more spending. If they didn’t remove that money - government spending combined with private sector spending would cause inflation.

As I’ve said already, all government spending is new money. What I haven’t said is that that new money isn’t a physical thing that has to be found.

Money isn’t a physical thing: explorers didn’t go out to find money, dig it up and bring it back so we could use it. Money is a concept, a unit of account, a store of value. It is a score card, a bit like the score card for a sports game. It counts how many, it counts what is owed, it counts what you owe, it counts what you have. And because it’s not a physical thing it can be digital, paper, metal coins or whatever else can fulfil the role.

So, to spend money, currency issuing governments don’t need to equip explorers to go out and bring back more money. After politicians decide what is to be done, the eventual spending process just involves typing figures into computer. The BoE uses a keyboard to create credits in the reserve accounts of private banks. And just as you and I can issue IOUs, there are no limits to the number we can issue, there are no limits to amount of currency a currency issuing governments can issue.

So where does that money comes from that the government spends? I’ve thought long and hard about this, and so as not to frighten the real economists, I’ve come up with a formula to explain it.

A human thought=money.

In our modern world all money comes from the people in government making decisions. Spending comes as result of someone thinking, ‘we need …”. If you are a conservatively minded, how would you finish that sentence? If you are left of centre progressive, how would you finish that sentence? Even non-discretionary spending (i.e., ongoing spending on welfare, pensions, national defence, foreign aid, education and transportation, and so on) is a result of decisions - made in the past - by politicians. Or before politicians, kings or other leaders who needed to resource their territory.

Politicians in government make decisions to spend money on whatever their priorities are and those spending decisions are carried out by the Bank of England. All spending - whether discretionary or mandatory, is new money - and that new money originated from a politicians noggin.

Spending decision are political. MMT reveals to us that as long as there is capacity in the economy - spending can be done. However, knowing how a car works, doesn’t determine your destination when you drive it. That’s the same with MMT. MMT can tells us how the monetary system works but it’s politicians who make the spending decisions. In a democracy those politicians were put in government by citizens.

So, we’ve learned that currency sovereign governments do not have limits to how much they spend. However, there are constraints. The constraints on that governments spending are real productive resources. The ultimate constraints are the finite resources of our earth.

Stephenie Kelton introduced the STAB and TABS acronyms, as a way to both remember and to describe the difference between how currency issuing and currency using government - who spend money and collect taxes. For currency issuers, spending comes first before taxes are collected. The acronym for this is STAB, i.e. Spending precedes Taxing And Borrowing. For currency using governments it is the other way around. The acronym is TABS, i.e. Taxing And Borrowing precedes Spending.

Issuing governments can’t run out of their own currency. You can of course have self imposed rules and you can run out of real resources to buy. The US for example, has put a legislative limit on the amount of national debt that can be incurred by the Treasury, limiting how much money the federal government may borrow to finance its operations. The common term for this is the ‘debt ceiling’. In practice, the debt ceiling is often broken. More often than not it is used for political leverage rather that to put restraints on spending, i.e., ‘if you pass additional spending we’ll vote for this other thing you want’.

Currency issuance and currency sovereignty are not the same thing. Currency sovereignty means a government can fully manage its economy through its own currency policies, including spending, taxing, and borrowing, without relying on foreign currencies or external financial pressures. Simply issuing your own currency is not enough. For example, if you have borrowed in a foreign currency, the debts you have accrued need to be paid back in that foreign currency. Your policy choices are constrained. For example, your agricultural policy may be orientated towards producing a particular types of food that is popular in the country you owe the debt to - while reducing the focus on staples for you own country. Your currency sovereignty will also be constrained, for example, if you need to import food or energy - which you have to pay for it in a foreign currency. The states power to exercise exclusive legal control over its currency, therefore is a continuum. Or, as an economist would put it, your ‘currency sovereignty is constrained’.

Currency sovereign governments don’t borrow to allow them to spend on goods and services. The purchase of a government bonds just swaps cash for interest-bearing bonds. This ‘swapping for an interest-bearing bond’ idea was one that took me a while to get my head around. But I did eventually figure it out, thanks to an excellent description in Stephanie Kelton’s 'book ‘The Deficit Myth’. However, as I don’t have that quote to hand, I’ll use my own more childish description. This is an explanation I wrote on a Facebook group: “buying bonds is not like buying a Mars Bar in a shop, where you get their Mars Bar and the shopkeeper gets your money. It’s more like you already own the Mars Bar and the shopkeeper just gives you a different wrapper for it. Now your Mars Bar has a Snickers wrapper on it and magically, you get income from owning the Snickers bar, instead of the Mars Bar.” I used this analogy because I was asked where the money went that was used to buy a bond. And I needed to think of a way to express the idea that the government was not actually being given money for the bond purchase. I.e., I was trying to explain that bond purchases were not a way for currency issuing governments to borrow.

Government bond sales do not finance government spending. As we found out earlier, a currency issuing government does not need to borrow its own currency. However, bond sales are useful. They take liquidity out of the private sector, i.e., the money used to purchase the bonds can no longer be spent for a stipulated period of time. This reduces spending - which can be helpful to control inflation.

MMT advocates are in favour of a Job Guarantee Program (JGP): anyone who wants to work can find employment via a government-funded JGP. It is MMT’s only explicit policy. The JGP acts as an ‘automatic stabiliser’ in relation to the business cycle due to the additional government spending involved - which increases aggregate demand within the economy’. The JGP sets a floor on private sector wage rates by providing a ‘living wage’ to all JGP employees. As economist Bill Mitchell, one of the founders of MMT, puts it: the JGP provides a ‘buffer stock of labour,’ ensuring that when the economy starts to recover, there is a pool of ‘job-ready’ workers for the private sector to employ. A JGP also addresses major social challenges linked to joblessness, such as poverty and mental health issues.

As the TV detective Columbo would say, “Just one more thing.” That one more thing is called sectoral balances. MMT brings attention to the following fundamental truth: the financial positions of the private sector, public sector, and foreign sector must always balance to zero. Put simply, a deficit in one sector must always be matched by a surplus in another. So, if the government is running a deficit, this will result in a surplus somewhere else — either in the private sector, the foreign sector, or both.

What’s your point Jim? My point is that the government deficit isn’t the villain it’s often made out to be. In fact, it plays an essential role in the economy. When the government runs a deficit, it pumps money into the economy, which ends up as a surplus in either the private or foreign sector. This is a direct challenge to the mainstream economic view, which sees government deficits as a problem. MMT flips that on its head, arguing that these deficits are crucial for economic growth and allowing the private sector to save. After all, the private sector can only save if the government is running a deficit, particularly when the economy isn’t at full employment.

Rather than worrying about deficits or trying to balance budgets, MMT sees a government deficit as a tool to drive economic stability and prosperity. This argument pushes against austerity thinking and suggests that deficits can and should be used strategically to maintain full employment, support growth, and create stability. It’s a shift in the conversation, away from deficit phobia, towards an understanding of the essential role government spending plays in the broader economy.

Stay tuned for more bullet points. This document remains open to additions.

References and resources

Social networks and keeping records of debts and obligations within communities.

Government spending reduces the availability of both goods, services.

Modern Monetary Theory: The Right Compass for Decision-Making

Origins of Modern Monetary Theory – MMT aimst to learn from the past.

In 2023 The Guardian estimated that deaths from austerity where close to 330,000.

Do you agree? Do you disagree? I welcome your comments either way. Please comment below.

If you’re finding value in these articles, become a paid subscriber. Your support allows me to continue to write, teach and to build a community of like-minded individuals—individuals, like you, who understand that MMT offers an opportunity to change the world for the better. Become a paid subscriber now.

Jim Byrne - MM101.ORG

He also doesnt like the term "Job Guarantee" because he would rather call it a transitional job.

Fadhel uses monetary sovereignty. He doesnt like that either.

Thanks for this! I kind of struggle with the idea that (Federal income) taxes are imposed to make me go to work to earn U.S. dollars to pay my income tax requirement. In our system, if I didn’t go to work at all, I wouldn’t earn anything, and I wouldn’t owe any taxes. I go to work because I want to eat and have a roof over my head, not because I owe taxes regardless of whether I work or not. I suppose it’s true that since the taxes I owe as a consequence of working must be paid in U.S. dollars, I am incentivized to work for dollars instead of bitcoins or something. But can you please explain again how the imposition of taxes in our system gets people to do what the government wants us to do (go to work in healthcare, making stuff etc.) in the first place? Or am I misunderstanding something? Thanks!