MMT Basics: National Debt – Defined and Explained

MMT Economics: Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) Reveals the Truth Behind the National Debt, Deficits, and the Myth of ‘Borrowing’

MMT Economics: What you will learn:

Why the term ‘national debt’ is misleading; bonds are a tool to manage interest rates, not fund spending; all government spending is new money, not financed by taxes or borrowing; issuing bonds is an asset swap; financial markets depend on government bonds; the real limits on spending are resources, not money; policy should focus on real outcomes, not arbitrary debt targets.

Technical Terms/Jargon Used in This Article

You will find definitions of all of the technical terms/jargon used in this article in my series of MMT Economic Jargon Buster articles. Paid subscribers can also download my MMT Dictionary.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) Explains Why the Phrase ‘The National Debt’ Is Misleading

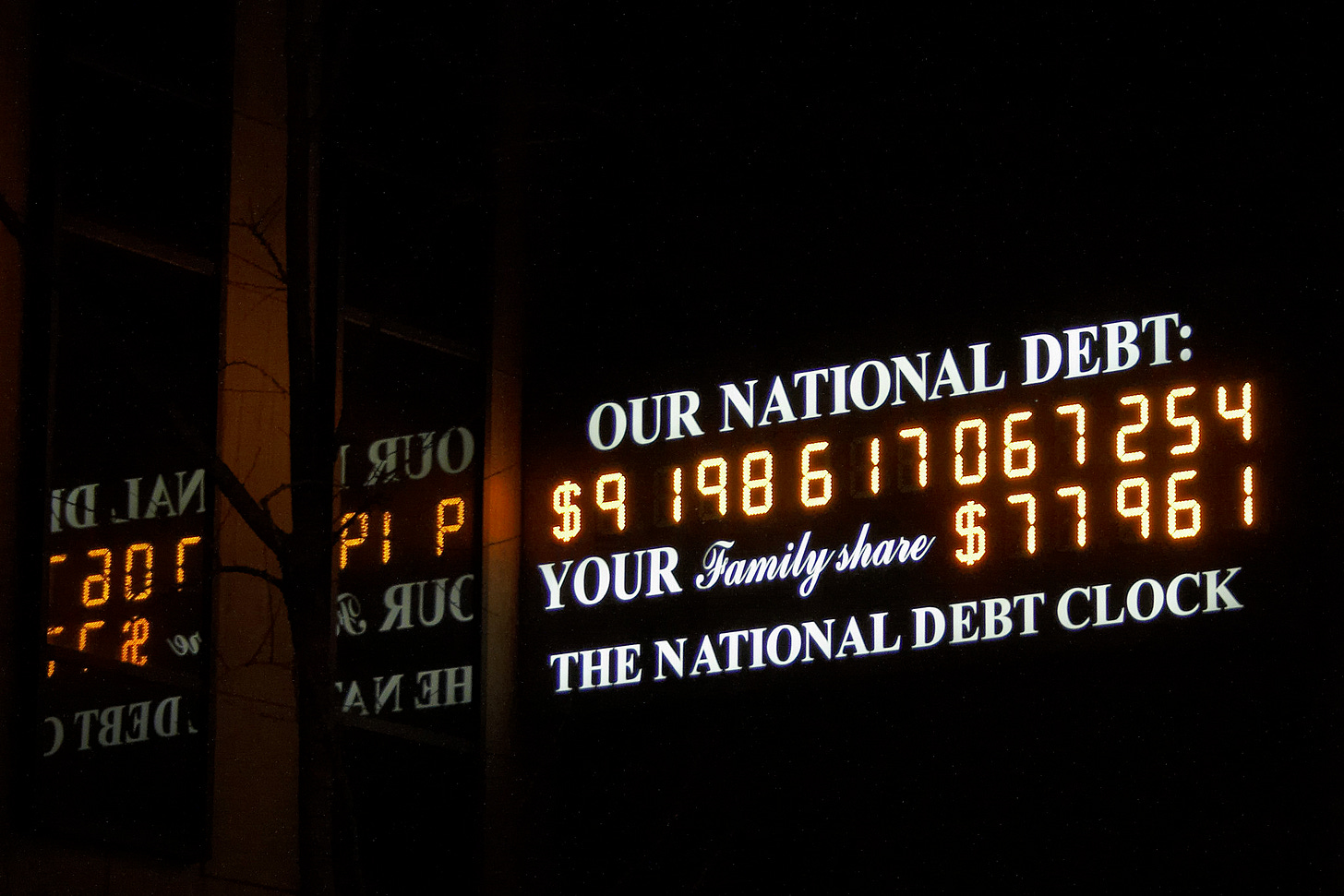

In this post I will cover the basics of what the mainstream media and orthodox economists call, ‘the national debt’. I will define what it is and examine the policy implications of that ‘debt’ both from an orthodox economist’s perspective and from a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective.

I will also explain why calling this debt the ‘national’ debt is misleading.

Defining the national debt

The ‘national debt’ tends to be defined in one of the following two ways:

The sum of outstanding government bonds, resulting from governments borrowing. What is a ‘government bond’. It is a risk-free investment guaranteed by the government. They are mainly bought by banks, pension funds, and other large investors.

The sum of all past government deficits. The government runs a deficit when it spends more than it brings in in taxes and other income.

Is the national debt figure the same for each of these definitions?

We are led to assume it is, because the common understanding is that when the government runs a deficit it borrows from the private sector to make up the difference between spending and income. However, there are a number of reasons why the debt figure for both of these debt definitions is different. For example, bonds are issued for reasons other than to close the gap between income and spending. Here are a few of those reasons.

In the US, certain spending is excluded from borrowing calculations

In the US, Social Security and other trust fund payouts are not ‘financed’ through bonds (MMT tells us that nothing is financed through bonds - but we will come to that later) and are generally excluded from “net federal borrowing” calculations. In the US, this ‘bakes in’ a difference between cumulative deficits and outstanding bond stock. Note that the UK does not follow this practice.

Spending can be carried out without the issuance of bonds

There are instances where the step of issuing bonds does not occur. For example, in the UK, during the Covid pandemic, the Bank of England (on instruction from the government) created reserves to pay for spending without ‘selling’ matching amounts of government bonds (because the government had to respond quickly to the Covid emergency). You can find full details of this process in my article, ‘Killing the Myth of Government Borrowing Stone Dead: Gilts, T-Bills, Interest Rates and the Truth About Money Printing’.

“when we came to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, and when we came to COVID, the government created money at will to meet the needs of our economy. And thank heavens that it did so. Therefore, there is no such constraint now.” — Emeritus Professor Richard Murphy

This practice confirms the core message of MMT, i.e., spending does not depend on the government having to ‘find the money first’, whether through the process of borrowing or from tax income. In reality, the issuance of bonds to match deficit spending is a convention—not a technical requirement; though that’s not to say that that convention does not have real and important uses.

In short, the private sector does not fund the government. All government spending is new money, which only comes into existence at the point private bank accounts are marked up with a payment from the government.

If you have any questions or if you disagree with anything I write in this article, I want to hear from you. Please add your comments in the discussion area. Contrary views are welcome.

Bonds are issued to help financial markets to work

Richard Murphy points out that bonds are also issued to ensure the health of financial markets. For example, the pensions market, overseas international trade, the life assurance market and the City of London. Without the government bond market the financial sector would not be able to operate at all.

Consider the fact that in the UK the financial and insurance services sector makes up approximately 8.8% of total economic output (GVA) - and broader estimates (including professional services like legal and accounting) push the combined share to around 12% of UK output.

So, government bonds help to ensure the health of financial markets.

“So, let's never pretend that the government is in hock to those markets, and that those markets can tell the government what to do. The reality is that those markets are utterly dependent upon the government to provide the savings mechanism that they need so that they can function. The power is all with the government, never with the financial markets.“ Richard Murphy - Funding the Future, Tax Research UK.

Does the difference between these two definitions of ‘the national debt’ matter?

Materially, there is little difference between the two ways of explaining the ‘national debt’—whether you look at total government bond issuance or total deficits. However, the latter narrative is more susceptible to manipulation. This bond-centric perspective easily lends itself to fear-driven rhetoric, such as claims that ‘the country is held to ransom by China' due to foreign-held debt. Such statements exploit misunderstandings of fiscal mechanics to create a false sense of vulnerability, overshadowing the reality that a sovereign currency issuer like the UK is not financially constrained by its bondholders. It also leaves no space for the idea that the governments debt can equally be defined as ‘private sectors savings’: i.e., it ignores the other side of the balance sheet.

Ok, that concludes the definition part of this post. While still being a simplified overview, hopefully that has added some useful information to the standard definition of what is referred to as the ‘national debt’.

Next, I’d like to examine the standard view of the role of government borrowing: what it is and what it is for.

Note, that paid subscribers resources are now on this page. Downloadable factsheets, a downloadable dictionary of economic jargon, my book/journal recommendations and much more.

Nothing gets borrowed when the government borrows

Despite the name, government borrowing does not result in additional spending money for the government. When the government issues bonds - as part of their government borrowing process – those bonds are swapped for the reserves that commercial banks hold in their central bank accounts.

This process does not increase or decrease the amount of money in the non-government sector. It just changes the composition of assets, converting reserves to interest-bearing bonds (note that banks also get interest on their reserves). It’s what financiers call ‘an asset swap’. If that doesn’t sound like ‘borrowing to fund the economy’ you are right.

When the US Department of the Treasury and the Bureau of the Fiscal Service Fiscal Data make the following statements on their website, they are wrong.

“The national debt enables the federal government to pay for important programs and services for the American public.” Fiscal Data at US Treasury

The only money generated by the ‘selling’ of government bonds is the interest paid on those bonds, which goes into the private sector. That is: money flows in the opposite direction from that indicated in the above quote.

The money used to buy bonds came from the government

Here’s an idea to keep a hold of: the money being used by financial institutions to buy those government bonds is the money that was originally spent by the government. Only central bank reserves can be used to purchase government bonds: and those reserves can only enter commercial bank reserve accounts via the central bank.

The government doesn’t need its own money back in order to buy stuff.

“As we know, governments spend by keystrokes that they can never run out of; a sovereign government that issues its own currency through keystrokes can never face a financial constraint. However, it can choose to “tie its hands behind its back” by imposing rules and procedures that limit its keystrokes. We should not be fooled by such self-imposed constraints.” Modern Money Theory – Randall Wray

Ok, we are on the home straight; I will finish this post by explaining why the phrase the national debt is a misnomer.

The phrase, The National Debt is a misnomer: the liability belongs to the government, the asset belongs to the private sector

"Government debt is just the money the government spent into the economy and didn’t tax back. That’s all the national debt is. It’s a historical record of all of the times that they made a net deposit, spent more than they taxed out, and the bonds are the difference between those." Stephanie Kelton – The Sanders Institute

It goes without saying that a nation consists of both the government and the private sector. And it goes without saying that for every liability (or debt if you prefer) on an accountant’s balance sheet there must be a corresponding asset.

We know who has the debt, the government. So who has the asset? The non-government sector has the asset - and the largest part of the non-government sector is the private sector (approx 97 to 98%). So, part of that asset is in your pocket and in your bank account. It is in the bank account of private sector businesses and it underpins the savings, pensions, and investments of households up and down the country. What gets called 'national debt' is, in reality, the financial wealth of the private sector.

When you add the government debt together with the non-government sector, what does it add up to? Yes, you are right - it adds up to zero: the governments liability cancels out the non-government asset.

So, is there a ‘national’ debt? There is certainly a government debt (a liability if you prefer that term) but it is not correct to say that there is a national debt.

What orthodox economists think government borrowing is for and what MMT economists think it is for

Orthodox economists regard government borrowing operations as literally borrowing money from the private sector. They view the government in the same way they view a household: if the government is spending more than it brings in, it must make up the shortfall by borrowing. That is, by selling bonds to the private sector and getting additional money in return.

What is the role of borrowing: the MMT view

MMT economists reveal that this is not how government borrowing works. Not only does borrowing not generate additional spending money, but the government does not need to borrow in order to spend. Currency-issuing governments such as the UK and US, by definition, issue their own currency.

The government creates money when it spends: all government spending is new money. In practice, government borrowing is largely a tool to manage interest rates, not to generate additional spending money.

Orthodox versus MMT - The Policy Implications

The mainstream economists view

Orthodox economists use the household analogy: spending has to be funded first, either by taxes or by selling bonds to make up any shortfall. Running deficits means accumulating debt, and as we all know, debts are a bad thing. Borrowing to pay off those debts has many implications for the economy.

When the government borrows, it competes with the private sector for available money, which raises interest rates, reduces funds for private investment, and increases demand in the economy. That increased demand pushes up prices. This is called the loanable funds model.

Policy advice, therefore, is to keep deficits under control, reduce debt, or make sure borrowing is “sustainable” compared with GDP. When government debt is ‘getting too large’ spending must be constrained, i.e., the government must enact austerity. This process degrades public services, reduces productive capacity, stunts growth - and has, in the UK, been shown to been connected to the death of thousands of citizens (Guardian, Oct 5th, 2022). An incorrect understanding of ‘the national debt’ leads to serious consequences for both the health of the economy and for citizens’ wellbeing.

Policy implications - the MMT view

From an MMT perspective, the loanable funds model is wrong: there is no limited pool of money:

Commercial banks create loans “from thin air” and are not constrained by the amount of reserves they hold or drawn from existing customers’ savings. Banks make loans when they are presented with a watertight business model presented by solvent individuals or businesses.

Government spending does not compete with private sector lending for a limited pool of funds. It does not need or get funds from the private sector. All government spending is new money created by the process of crediting private sector bank accounts.

The conclusions implied by orthodox economics, in relation to deficits and the need for borrowing, are incorrect. Interest rates are determined by the central bank and not by the quantity of government borrowing. Inflation is only a risk if the economy is at full resource capacity, and not because the government runs a deficit.

MMT shows that the real limits on spending aren’t money, but the availability of real resources: workers, materials, and productive capacity.

Policy from this perspective focuses on putting money to work where it achieves real outcomes, like full employment, better infrastructure, and social programs, while using fiscal and monetary tools to manage inflation rather than obsessing over “debt levels.”

In Conclusion: What Have We Learned About ‘The National Debt’?

Here are ten things we have learned from this post:

The “national debt” label is misleading: the liability belongs to the government, the asset belongs to the non-government sector.

It’s described in two ways: total outstanding bonds or total past deficits. They are not the same, but materially, the difference doesn’t change the story - however the latter definitions makes for a better scare story.

Bonds are a tool for managing interest rates, not for funding government spending.

All government spending is new money created by crediting private sector accounts; it is not financed by tax revenues or borrowing.

The money used to buy government bonds originally came from government spending. This is literally true, because all money in commercial bank reserve accounts was created by the central bank on the government’s orders. Only money held in reserve accounts can be used by banks to settle purchases of government bonds.

Borrowing doesn’t increase money in the economy, it’s just an asset swap.

Financial markets depend on government-issued bonds; the government holds the power.

The real limit on spending is resources: workers, materials, and productive capacity, not money.

Government borrowing does not create inflation by itself. Spending only risks inflation if the economy is at full capacity.

Policy should focus on real outcomes: full employment, infrastructure, and social programs, not arbitrary debt or deficit targets.

What we have learned from this post is that there is no such thing as the ‘national debt’. It is neither national nor is it a debt in the conventional sense of the word, i.e. the way a household or business would use it. However, the implications of the misunderstandings are significant, both in terms of the policies that flow from that misunderstanding - and the effects of those policies on the wellbeing of citizens.

That’s all for now. Don’t forget to subscriber for more MMT economics related content from MMT101.

Resources

Why do governments issue bonds when they don’t need to? - Richard Murphy

The Sanderes Institute - Stephanie Kelton Wants You To Rethink The Deficit.

Links to some of my most popular newsletters

Become a paid subscribers for access to additional content:

A Permanent Home for MMT101 Paid Subscriber Resources – Factsheets, book recommendations, academic papers, MMT podcasts and more.

MMT Factsheet 3: If Taxes Are Not For Spending What Are They For?

Excellent! I'd also point out that the interest paid on bonds goes to the wealthy end of the private sector. In other words, interest rates are the opposite of progressive. Although outside of the scope of an article explaining debt, this would lead on to why Warren Mosler's ZIRP proposal should be adopted.

The statement "the issuance of bonds to match deficit spending is a convention" gives the impression that in normal times additional bonds are issued to match the current year's budget deficit. Is that what the author meant? If that were the case, wouldn't that suck money out of the economy equivalent to the budget deficit, thereby nullifying the monetary effects of the deficit?