Does MMT Really Tell Governments to Spend, Spend, Spend, Without Limits — Or Is That Just Nonsense?

MMT Economics: Debunking the myth that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) encourages governments to spend without limits

MMT Economics: What you will learn:

An understanding of what Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) actually says about government spending; why MMT does not advocate unlimited spending; why real resources and inflation are the true constraints on spending for monetary sovereign governments; why taxes still matter under MMT; and how critics often misrepresent MMT’s position by ignoring its core principles.

Technical Terms/Jargon Used in This Article

You will find definitions of all of the technical terms/jargon used in this article in my series of MMT Economic Jargon Buster articles. Paid subscribers can also download my MMT Dictionary.

Addressing the critics of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) by revealing what MMT actually says

“MMT has been argued to be both fascist and communist, orthodox and heterodox, dangerous and benign, unworkable and obvious, and unrealistic and clearly nothing new. “ Eric Tymoigne

Apart from Marxism, is there any other school of economic thought that has attracted more criticism from mainstream economists than Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)?

I suspect not. For example, former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers called MMT “dangerous.” Nobel Prize-winning economist and New York Times columnist, Paul Krugman has repeatedly criticised MMT in the New York Times and elsewhere. And both the ‘Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’ (more commonly called the OECD, an organisation of 38 countries set up to improve economies around the world) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have released papers or statements warning against MMT-style policies.

MMT never fails to get hit by both barrels when mainstream economists take aim. So, with that in mind – and because this was a topic mentioned in replies to my subscribers questionnaire – I intend to address some of the most persistent criticisms in a series of articles/newsletters.

I will start this newsletter series by addressing the idea that MMT encourages governments to indulge in deficit spending (defined as spending more than taxes bring in) and that this is a misguided and dangerous approach to managing government finances.

This standard MMT diktat is misguided - say mainstream economists - because it causes inflation, it crowds out private borrowing (and thus investment), it increases the national debt and, most importantly, it endangers the ability for the government to borrow to fund public services.

I will be addressing each of these points in turn shortly but, first, we need to address the most basic of questions: does MMT actually tell governments they can spend beyond their means? I.e. does MMT recommend deficit spending as the default fiscal policy?

If you have any feedback or questions or if you disagree with anything I write in this article, I want to hear from you. I value your input whether you agree with me or not. Please add your comments in the discussion area.

Does MMT Recommend Deficit Spending?

The short answer is no. In fact, MMT does not advocate any particular level of spending - whether it is a deficit or a surplus - because MMT is focused on the real economy and what it needs at any particular time. MMT recommends the level of spending that is required to make the most of the nation’s resources: the level of spending that is required to meet the government’s goals.

What does MMT say about the role of fiscal policy (taxing and spending)?

MMT draws heavily from the work of Abba P. Lerner - and his ‘Functional Finance’ approach. Lerner states that governments should spend with real goals in mind. They should not design their fiscal programs around spending targets – or around the spurious idea that governments must run balanced budgets.

So, the goal might be to ensure that everyone who wants a job has one or the country has an effective public health service. Whatever spending and taxation plan is required to reach those goals is the appropriate level of spending. The aim should not to be to set a goal for a balance between spending and income, the goal should be based on the real needs of citizens and the health of the economy.

In my profile of Lerner I wrote the following

“For Abba P. Lerner, the correct level of government spending and taxation is that which is needed to achieve full employment and price stability. The focus of government spending policy should always be on real outcomes in the real economy - not arbitrary goals – such as balancing the budget or achieving a particular deficit size. From Lerner’s point of view, the size of the deficits (or surplus) is an outcome of a full employment policy, not a goal in itself.” Jim Byrne - Important Figures in the Development of MMT: Abba P. Lerner ‘Functional Finance’

Economist Pavlina Tcherneva put it more succinctly than myself, ’we must judge fiscal measures by the effect on human activity, not by the effect on the budget.’

MMT would also point out that, historically, deficit spending has happened, not because it was an overt government goal (and anyway, a deficit is something you only discover after the accounting period ends), but because the health of the economy often ‘forces the governments hand’. For example, governments across the world were forced to deficit spend due to the Covid pandemic.

Even without global shocks, governments that do not have trade surpluses (I.e. foreign trade accounts that add net income to the private sector) are likely to be wrong-footed by the private sector’s tendency to save. Private sector savings withdraw spending from the economy and, if that is not addressed, it leads to reduced overall demand, which leads to slowing growth.

So even in normal circumstances, if the private sector wants to net save, and the country is not running a trade surplus, the government must run a deficit to sustain demand and enable economic growth.

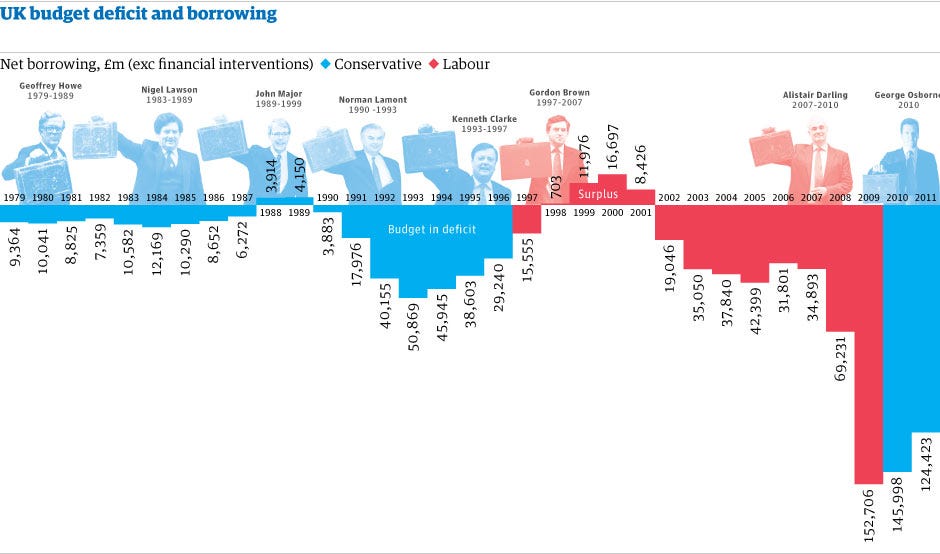

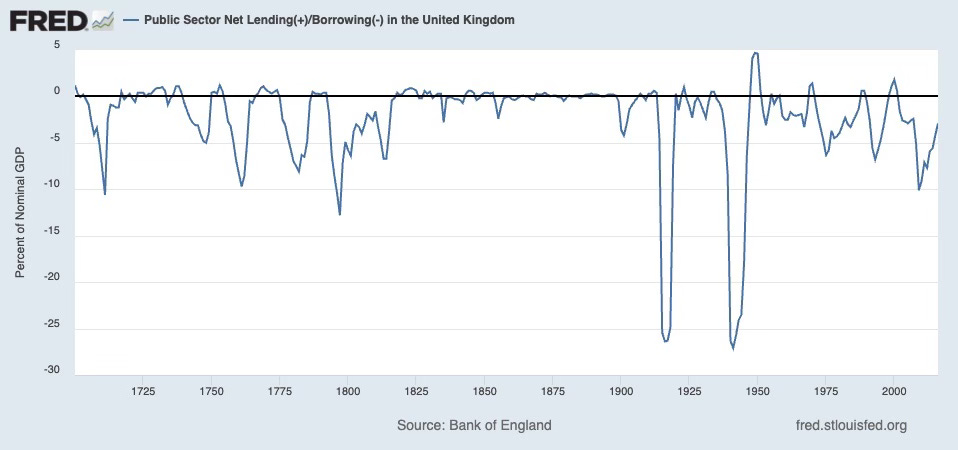

This is why, when we look at the data, we find that most governments have historically ran deficits.

Note, that paid subscribers resources are now on this page. Downloadable factsheets, a downloadable dictionary of economic jargon, my book/journal recommendations and more.

Historical data reveals that deficits are normal and are the default position for currency issuing governments

MMT highlights that, in countries that run trade deficits, and there is a propensity within the private sector to net save, continuous deficits are required to support economic growth.

Now that we have established that the premise of this criticism is incorrect, I will address the beliefs that orthodox economists use to support it.

Even if MMT did encourage deficits, what’s the problem with that?

Mainstream economists think that running deficits, as a default policy, is an inherently a bad idea. These criticisms are based on the following beliefs:

Deficits cause inflation i.e. government spending means more money chasing the same amount of goods and services.

Deficits crowd out private sector investment. This belief is based on the idea that before a government can spend it has to borrow. And that borrowing competes with the private sector for a limited pool of saving.

Deficits increase the national debt. And mainstream economist belief that that debt will have to be paid back at some point in the future - or a time of reckoning will come.

Deficits make the government look profligate in their management of public finances, which erodes confidence, making it harder for the government to raise funds. This lack of confidence could lead to a debt crisis and ultimately a government that can become bankrupt.

I’m not saying that there are not mainstream economists that see the benefits of deficit spending during an economic downturn, there are - but as a general approach they think it’s a bad idea and they think that MMT economists are wrong to recommend it. Ok, let’s examine each of these criticisms in turn.

1. Deficits will cause inflation

Both MMT and mainstream economists agree that trying to buy scarce resources will push up the prices. When demand outstrips supply, sellers know that they can set a higher price, and still sell their goods and services. If you are a government and you want to buy more oil when it’s scarce you’ll have to pay a higher price.

The difference between orthodox economists and MMT economists is that orthodox economists focus on the spending side of the equation, while MMT economists focus on the resources side.

MMT economists say it's not the spending per se that causes inflation – it doesn’t matter how much you spend – as long as there’s enough capacity in the economy to absorb it. What causes inflation is not the spending itself - but the availability of things to buy. When resources are scarce prices go up.

Orthodox economists, on the other hand, have a tendency to focus, not on the resources, but on just how much money is being spent. Specifically, they become concerned about size of that deficit in relation to GDP.

As a result they are keen on imposing constraints on spending, i.e. ‘deficit limits’ - most often expressed as a percentage of GDP.

For example, historically the EU has had a 3% of GDP deficit rule for spending by Eurozone countries. However, there is no evidence to suggest that this figure is based on empirical data (seek out work by economist Dirk Ehtnts for the source of this idea and this EU deficit figure). The number chosen was a political choice, not a technical one, and it is based on past conventions rather than any real evidence related to the impact of deficits.

“The point is to implement the public purpose at a pace that recognises the potential constraint that comes from domestic resource availability and potential inflationary pressures from bottlenecks, rising import prices, and exchange rate depreciation, among others.” Eric Tymoigne Seven Replies to the Critiques of Modern Money Theory

MMT recognises the importance of managing inflation

So, MMT recognises that fiscal policy does indeed have to be managed to avoid inflation. However, it does not posit that it is finances that are scarce, nor that there should be artificial limits put on spending, nor that the government should focus on achieving a particular surplus or a deficit figure. MMT says that governments should put their focus on their real goals - while staying within the consumption limits of available resources.

“If I had to describe the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) project in a single sentence, I would say it is about replacing an artificial revenue constraint with a real inflation constraint… But the limit is not a predetermined numerical level or a percentage of the budget. There is no strict financial constraint. A currency-issuing government can afford to buy whatever is priced and available for sale in its own currency. The limit is the impact of the spending. Not the spending itself, and not the deficit—the limit is inflation. That is central to MMT.” Stephanie Kelton - Dissent Magazine

Don’t forget to subscribe. If you are finding these newsletters useful and want to support me to continue to write and teach MMT, please become a paid subscriber. It helps me to continue my quest to help as many people as possible to understand how our monetary system works.

2. Deficits lead to government borrowing which ‘crowds out’ private sector borrowing

This is the idea that when a government runs a deficit, it has to borrow in order to fund its spending, and that means it competes for limited funds with the private sector. Additionally, competition for funds pushes up interest rates, which makes it even harder for private sector businesses to obtain the investments they need to grow.

Private sector businesses are, therefore, crowded out from obtaining the funds they need by the government’s borrowing needs.

There are two problems with this story. First, commercial banks do not lend from limited funds i.e., they do not lend from a finite pile of existing savings. Instead, they create money ‘from thin air’. When a creditworthy business or individual comes along with a credible plan, the bank records a loan as an asset on its balance sheet and simultaneously creates a deposit (i.e. new money) in the borrower’s account.

Apart from capital requirements and banking regulations there is no limit to the amount of funds available for investment, i.e. there is no limited pool of available funds – as is believed by some mainstream economists.

The idea that government borrowing pushes up interest rates is also incorrect. In reality, the central bank sets the base interest rate as a policy decision. Interest rates don’t get pushed up because the government borrowing is “crowding out” the private sector and in the process making borrowing dearer for everyone.

Government spending is not funded by borrowing

Secondly, the government spending is not funded by borrowing. All government spending is new money. Currency issuing governments do issue bonds but they are used as a policy tool to control interest rates via the overnight interest rate (i.e. the rate at which banks lend to each other).

And the government is not growing out private sector investment and thus hurting economic growth: on the contrary, government spending increases demand, improving infrastructure and employing underused resources.

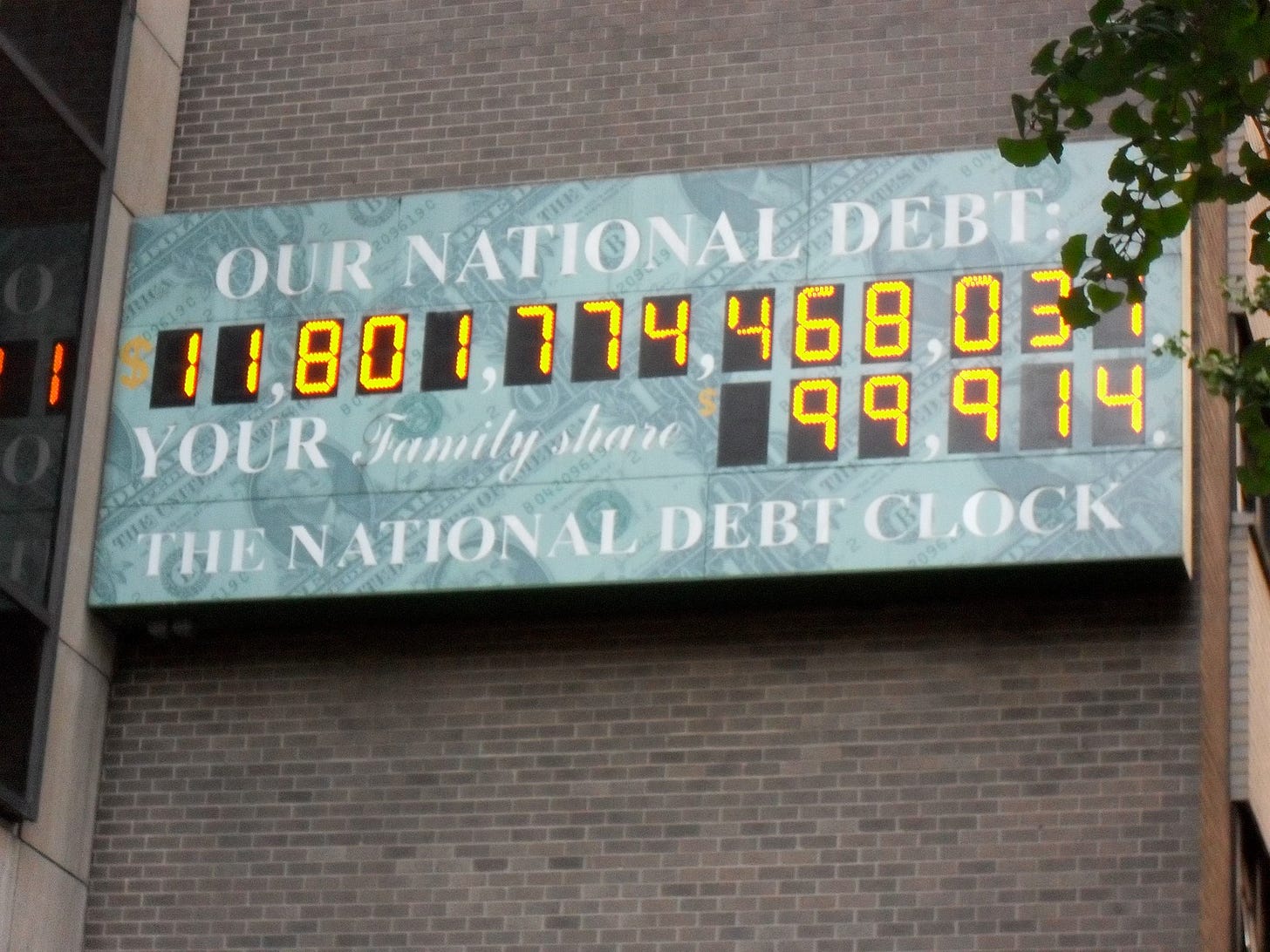

3 Deficits increase the national debt

“This is the National Debt Clock, right? The sum total of all of the outstanding bonds that the Treasury has issued…we shouldn't call that the National Debt Clock we should just rename it. It's the national World dollar savings account…” Stephanie Kelton speaking at the Fiscal Sustainability Conference 2010

When neoclassical economists talk about the national debt, they assume that governments operate in the same way as households or as businesses getting a loan to invest for growth, which they have to pay back. If loans are not paid back there will be dire consequences (such as mortgage holders losing their homes or businesses going bankrupt).

However, that assumption is wrong. It is wrong primarily because, unlike households, governments like the US or UK Governments, are the monopoly issuers of their national currency. Meaning that they don’t have to borrow money before they spend.

For example, If my wife Pat had a printing press that churned out £10 notes - assuming we both didn’t get arrested for counterfeiting – I could spend that money in my local corner shop to get ‘the messages’ (Google, ‘getting the messages’). For as long as we both stayed out of jail, neither of us would ever need to earn or borrow money in order to spend. Similarly, neither the US nor UK Governments have to earn or borrow money before they can spend.

As Stephanie Kelton and other MMT economists point out: the ‘national debt’, as represented by the debt clock (located on the western side of the Bank of America Tower in Manhattan) is not a record of debt in the ‘tradition’ sense of the word. Instead, what it represents is the net amount of money that the US government has spent into the non-government sector - and primarily that means the private sector. Because when the government spends, that spending has to go somewhere, and where it mostly goes is into the private sector.

It is a debt in the sense that it is recorded as a liability on the government’s balances sheet - but it is not the same as household debt. One crucial difference is that it never has to be paid back. It is a debt that can exist on the government’s spreadsheet forever - without it ever affecting the government’s ability to spend in the future.

So, when neoclassical critics warn that deficits are dangerous because they increase the national debt - they are misunderstanding the nature of the government’s liability.

What would happen if the government debt was fully repaid?

Defining the phrase ‘government debt’

Before answering this question I need to mention that the phrase government debt tends to be defined in two different ways. Traditionally, it refers to the value of the debt that results from government borrowing, that is, the total value of bonds issued by the government in exchange for bank reserves.

However, MMT economists, while recognising this conventional definition, often define the government debt in a broader way, defining it as the difference between what the government spends into the non-government sector and what it takes back out through taxation. In that sense, the national debt represents the net financial assets remaining in the economy – the money left in the non-government sector after taxes have been paid.

I mention this as it gives us context in order to understand my next point, which is about what would happen if the government debt was actually paid off.

If we were to follow the advice of neoclassical economists, who urge us to ‘extinguish the national debt’, i.e. reduce the figure in the consolidated government debt spreadsheet down to zero, it could be done in the following way:

Firstly, the government could run continuous budget surpluses i.e. taking more out of the non-government sector in taxes than it spends in each accounting period.

Secondly, the government could instruct the central bank to stop issuing new bonds and let all existing government bonds expire. This would ensure that no further ‘government debt’ was issued. It would also ensure that no further interest on government bonds would get paid into the non-government sector.

Despite running a surplus, which removes money from the private sector, it would take some time to extinguish the flow of economic activity or growth – as the private sector would initially take on debt to replace that removed by the government (and there may also be earnings coming into the country from foreign trade). But eventually, as growth slowed and private debt reached a point at which it cannot be rolled over or paid back, the national debt would be eliminated. And the economy would grind to a halt.

Banks, as we are reminded by mainstream economists, may well be in a position to find loans but as MMT economists remind them, those loans do not add any net money to the economy - as they have to be paid back. Loans are real private sector debt. And, unlike the government’s liabilities, they do indeed have to be paid back.

So, now what you end up with is unmanageable private sector debt. And that means people losing their homes, businesses are going under, unemployment is going up and the financial industry in meltdown.

Attempting to repay the national debt is not a good idea. In the 1990s, President Clinton attempted to run a government surplus, aiming to reduce the national debt — as recommended by the neoclassical and mainstream Keynesian economists of the time. However, the policy was scrapped as unemployment rose and the economy weakened.

4. Deficits make the government look profligate in their management of public finances

This particular criticism is based on the misguided idea (in the view of MMT advocates) that governments should aim to run balanced budgets in order to keep (mostly) bond traders happy. Because it is bond traders that enable the government to borrow. And without that borrowing, the government would be unable to spend on public services.

So, a fiscally responsible government, from the orthodox economist’s point of view, is one that strives to run a balanced budget, by ensuring that there is enough income from taxes to cover all government spending.

A fiscally irresponsible government, on the other hand, i.e. one that continually runs a deficit, which will make it harder for the government to sell its bonds - due to the message it sends out to the financial markets. Traders will demand a higher return from their investment because they now see their purchases as more risky. I.e. the government could conceivably fail to pay the interest on their purchases. Ultimately, the government could even become bankrupt.

And all because the government took the advice of MMT economists and ran deficits by default. Let’s examine this idea via a story that Warren Mosler tells in his book ‘Soft Currency Economics’.

The story of Warren Mosler Italian Government

If you think the above story sounds implausible, I recommend the you read Warren Mosler’s book ‘Soft Currency Economics’ in which he tells the story of the situation that the Italian government found itself in in the early 1990s. At that time, Italian government bonds were trading at steep discounts due to fears of default.

Mosler understood that Italy, as an issuer of its own currency, could not default unless it chose to do so. On a trip to Italy he met with officials at the Italian Treasury - and confirmed this to be the case – reassuring the Italian government that a default was not inevitable.

In short, he confirmed that bond sales are not needed for the government to raise funds - and that the government could not go bankrupt. It should be noted that this event is often seen as the beginning of MMT – as a school of economic thought.

In conclusion: MMT does not tell governments that they should spend, spend, spend!

“ In all cases, when monetary sovereignty prevails, the fiscal position and the public debt are poor metrics for judging the viability of a public purpose and its pace of implementation.” Eric Tymoigne Seven Replies to the Critiques of Modern Money Theory

MMT does not recommend that governments should indulge in reckless spending – or indeed any specific spending recommendation. But rather, fiscal policy should be guided by the economy’s real needs. If that means boosting employment, supporting public services or spending on infrastructure, then the level of spending will be determined by what is needed to meet those goals.

By debunking this common criticism, we can have a conversation about how governments can best manage their finances to support citizens and the economy – rather than spending endless hours debating the power of ‘predatory bond traders’ to derail the government’s spending goals.

Understanding MMT’s approach means we can move beyond conversations about what we can’t do – because there is a ‘black hole in the finances’ – toward conversations about what we can do. That is, conversations about what needs to be done to help improve citizens’ lives.

That’s all for now.

If you have any feedback or questions or if you disagree with anything I write in this article, I want to hear from you. I value your input whether you agree with me or not. Please add your comments in the discussion area. And don’t forget to subscribe for more MMT economics learning from MMT101.

Links to some of my most popular newsletters

Become a paid subscribers for access to additional content:

A Permanent Home for MMT101 Paid Subscriber Resources – Factsheets, book recommendations, academic papers, MMT podcasts and more.

MMT Factsheet 3: If Taxes Are Not For Spending What Are They For?

Humans are susceptible to a few characteristics. We blame and scapegoat. We reify theories and we set up competing social constructs to explain reality — my reality is better than your reality.

There are a few humans who examine facts and use science, mathematics and research to explain reality.

Unfortunately it seems those who rely on facts and actual accounting data are scarce amongst the economists who often are competing to put forward and market their preferred social construct of reality.

This article and others by Jim (and other MMT folks) are good efforts to critique the conventional wisdom — another way of describing social constructs.

Originally, I was going to say Austrian economics, but then I realised you said 'criticism from mainstream economists'.