The Myth of Barter & the Origins of Money – Fundamentals of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)

Part One: Money Evolved as a Natural Response to the Flaws of Barter

After last week's Eurozone detour, I feel obliged to get back to basics. This week, that means I’ll be trying to figure out the origins of money. Which feels like ground zero for a Modern Monetary Theory advocate like myself.

Our journey towards enlightenment – as far as understanding where money came from – will be via the two main stories about its origins outlined by C.A.E. Goodhart in his paper, ‘The Two Concepts of Money, and the Future of Europe’. Those stories are, the ‘Metallists Theory of Money’ and the ‘Chartalists Theory of Money’.

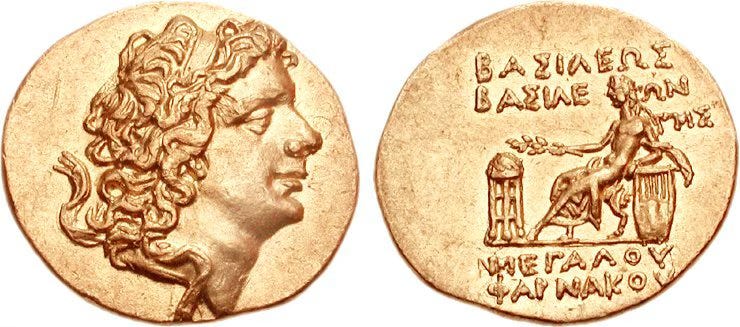

In this article, I explain the Metalist Theory (so called because historically it has been equated with coinage) and in a later article I will cover the Chartalists Theory of Money.

If you have any questions or if you disagree with anything I write in this newsletter, I want to hear from you. Please add your comments in the discussion area.

Orthodox Economics Assumes That the Metalist Theory of Money Is Correct

The Metalist Theory of money (i.e., money resulted from the flaws of barter) is the default story taught in universities, colleges and schools. It is the story that underpins the ideas and assumptions used by orthodox and neoliberal economists. And if you Google, ‘where does money come from originally’ it is the story you will find in your search results. The Metalist Theory of Money dominates the discourse.

However, as has been pointed out by Steven Hail, Alfred Mitchell-Innes, Georg Friedrich Knapp, John Maynard Keynes, David Graeber and all MMT advocates, the barter story is wrong. Despite its ubiquity, there is no archaeological or anthropological evidence to back it up. (I thought I’d better mention this now, rather than potentially lead you astray). Later in this article, I’ll ask the important question, i.e. if it’s wrong why is it still the dominant story? For now we will find out what the Metallists’ Theory is.

Note, that paid subscribers resources are now on this page. Downloadable factsheets, a downloadable dictionary of economic jargon, my book/journal recommendations and more.

Defining the Terms: Metallists and Chartalists

Here are some definitions to give a solid foundation for our exploration.

Definition of the word ‘Metallist’: The word "Metallist" is derived from the Latin word metallum, meaning "metal." The term was used by Carl Menger in his 1871 work Principles of Economics to describe the view that money derives its value from the commodity it is made from, such as gold or silver. According to the Metallist theory, money has 'intrinsic value’ because of the material it is composed of, and its role as a medium of exchange arises from its desirability and inherent properties. A 'Metallist' perspective sees money as a tangible commodity, valued for what it is made of, rather than for any external authority or decree. (If I was being pedantic, I might consider the phrase ‘intrinsic value’ a misnomer: as it is always people who decide whether something is of value or not. What we can say though is that there is general agreement that rarity, durability, divisibility, uniformity and usefulness are valuable attributes of metal in this context.)

Definition of the word ‘commodity’: a physical good with ‘intrinsic value’ that can be traded or exchanged.

Definition of the word ‘Chartalists’: The word Chartalists comes from the Latin word charta, which means 'token' or 'paper.' It was in Georg Friedrich Knapp’s The State Theory of Money (1905) that the term Chartalism became explicitly linked to the idea of state-issued money. Knapp argued that money derives its value from the authority of the state rather than from its material content. Money, he wrote, is a token (charta) accepted because the state designates it for payments, particularly taxes. A ‘token’ is something (a physical or digital object) that represents something else—whether it’s value, permission, membership, or obligation—rather than having any intrinsic worth of its own.

Ok, we have our basic definitions. It’s now time to put the ‘pedal to the metal’ and speed this thing up a bit. We need to learn about the barter system and how it naturally led to the ‘invention’ of money.

The Barter Story and the Origins of Money

I previously describe barter in my article, ‘Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) in 67 Bullet Points’, so rather than finding a new way to repeat myself, here is what I wrote.

What Is a Barter System?

“In a barter system if you are a carpenter, and need food for your family, you exchange a chair or some other wooden piece you’ve made, for food from the farmer.

If you are a blacksmith and want a musical instrument, you give the instrument-maker a hammer, a poker and a spade, and he’ll give you a guitar.

Of course, if you think about this for more than a few minutes you start to realise that you have no future as a guitar player. Sorry, what I meant to say was; you will realise there are flaws in this system.

If you want food but the farmer doesn’t want wooden furniture or you want a guitar but there aren’t any guitar makers to trade with, that’s a problem.

Think about it for a few minutes more and you might realise that in every transaction - both parties must have the goods or services that the other wants. This is called the ‘double coincidence of wants’ problem.

A few more minutes and you’ll start worrying about how the boat building knows how many chickens his boat is worth - and where to find the man or woman with all the chickens. And now you are thinking about how the cobbler can divide up his boots when he only wants one apple from the orchard. It’s getting complicated. That’s called, the indivisibility problem.

You just need to figure out how much everything is worth (that’s called, the need for a common measure of value) and you can exchange the shirt you made for a certain number of coins, then you can buy the lettuce from the market gardener.

The market gardener can accept your money, save it along with all the money he/she has made from other transactions and buy that boat.

And now the boat builder can buy his chickens. And finally; you can buy that guitar you’ve always wanted.”

Money Comes to the Rescue: Now We’re Coining It In

Even a humble MMT enthusiast like myself, can spot the flaws inherent in the barter system. However, all is not lost (yes, the boat builder will get his chickens). Because it is these very flaws, orthodox economics tells us, that naturally led to the evolution of money.

All that was needed, was an intermediary commodity. A commodity that could solve the double coincidence of wants’ problem, a commodity that could sort the the indivisibility problem and a commodity that could provide a common measure of value. Hey presto - all of these things can be solved with money - principally in the form of gold coins. Gold coins are the answer: and it’s an answer that evolved naturally from the flaws of barter. Gold coins make trade easier because:

Being something that everyone will accept. They have value beyond their face value.

They solve the problem of needing to find someone who wants exactly what you have. As long as you can find someone who has what you want and you have enough gold coins to pay for it, you can buy it.

They let you buy things in smaller or bigger amounts. You just need different sized gold coins representing different values.

They can make it clear how much goods are worth: even though they are all different in nature and are worth different amounts.

They are durable. You can depend on gold to stay the same over time. It doesn’t rot.

They are portable and can be made in uniform shapes and sizes. Gold can be fashioned into coins of different sizes and values and they are easy to carry around.

Money: It’s Not Just About Metal Coins

And, ironically (given the Metallist nomenclature and the connection with coinage), any commodity can be money - as long as they have the above attributes.

So, not just gold or silver, but also things like shells, salt, beads, cows or whatever else fits the role. If butter had the appropriate attributes, I could exchange my butter mountain for a new car. But it doesn’t and I can’t. And anyway I don’t have a butter mountain (enough Jim, enough, you’re not funny).

Barter Flaws Solved! Money Is the Answer to All of Our Problems – or Is It?

So, this feels like a reasonable story. It doesn’t feel outlandish to say that money naturally evolved from the flaws of the barter system - if I didn’t know any different I could easily believe it. However, there’s one fly in the ointment. There’s no evidence to support this story. Damn!

If you’re finding value in these articles, become a paid subscriber. Your support allows me to continue to write, teach and to build a community of like-minded individuals—individuals, like you, who understand that MMT offers an opportunity to change the world for the better. Become a paid subscriber now.

But Is It True? Did Money Evolve Naturally from Barter?

Caroline Humphrey, a renowned anthropologist and professor at the University of Cambridge, and author of the 1985 paper "Barter and Economic Disintegration" stated:

"No example of a barter economy, pure and simple, has ever been described, let alone the emergence from it of money; all available ethnography suggests that there never has been such a thing.” Man, New Series, Vol. 20, No. 1 (Mar., 1985), pp. 48-72

French sociologist Marcel Mauss, and Cambridge political economist Geoffrey Ingham have said more or less the same thing. In his essay, ”The Gift”, Marcel Mauss examines exchange systems in archaic societies, highlighting that these societies operated on principles of gift-giving and reciprocity rather than barter. Similarly, Georrfey Ingham writes that money did not emerge directly from barter systems but rather from complex social relations and credit systems.

The general agreement is that not only did money not evolve from barter but markets did not exist prior to the emergence of money. It was money that came first, markets came later.

Outwith the discipline of economics, it is agreed that money did not evolve from barter. No studies have been unearthed that show any societies where market-style exchange was based on a barter system.

“In most of the cases we know about, [barter] takes place between people who are familiar with the use of money, but for one reason or another, don’t have a lot of it around,” David Graeber, an anthropology professor at the London School of Economics.

It’s Time to Examine the Assumptions That Underlie the Barter Story

The idea that money evolved naturally from barter systems is starting to look a bit shaky. I think it’s time we examined some of the assumptions behind the story to see if they hold up:

Markets have always existed, i.e. past human behaviour is the same as present behaviour. Historical evidence suggests that societies have primarily been organised around social, political, and institutional structures not markets. David Graeber in his book “Debt - The First 5000 Years” writes not about markets but about gift economies and reciprocity.

Society is made up of individuals, each specialising in goods or services that can be traded for other goods or services. Even modern economies do not operate as a set of individuals independently producing and selling goods and services. What we have are businesses and states organising the production process. Individuals do produce their own goods and services but this is not the norm. The evidence suggest that most economic production has historically been collective. For example, in feudal societies, serfs worked within a system of obligations to lords and monarchs.

Trading is a natural human impulse. Humans have an inborn desire to “truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another.” said Adam Smith Perhaps that is the case, however, many societies have operated without significant trade. Communal sharing and state-administered provisioning have been historically common.

Trade is conducted directly with the individual who has the goods you want. I.e. this is the idea that barter was the common trading method. As I pointed out earlier, there is no anthropological evidence for this vision of a trading society based on individuals trading with one another.

There was an agreed exchange value between all things produced or that value could be discovered through negotiation. Even at a very basic practical level this seems unlikely. In this individualistic society - who was it that gathered all of the data relating to what every individual produced – and then published the ‘menu of comparative values’ between products? This is a complex and impossible task. Or maybe nobody did that - and each individual negotiated a price for each transaction. Could you negotiate a price for each item in your weekly shopping basked - not with the shop owner but with each individual who produced the product? And also have something of you own to trade for each product you needed?

There’s No Evidence That Barter Was Ever Used as a Market System

People have always used barter, and still do, that is true. However, there’s no evidence than societies ever used barter as a general market system. Or that money spontaneously developed from it. David Graeber in his book, ‘Debt: The First 5000 Years’. explores the historical and anthropological origins and implications of debt and money systems. He presents evidence that suggests money appeared out of social and moral obligations within communities. It was related to the creation and canceling of debts within communities. It was not simply an economic transaction, it was a social and moral construct.

“On one thing the experts on primitive money all agree, and this vital agreement transcends their minor differences. Their common belief backed up by the overwhelming tangible evidence ,.. is that barter was not the main factor in the origins and earliest development of money.” (Davies (1994) A History of Money: From Ancient Times to the Present Day).

Why Did the Barter Story Appeal to Economists, and Why Has It Persisted Despite Evidence That the Story is Wrong?

“The main advantages of the M-form theory appear to be technical, in that it lends itself to better mathematical formalization, and ideological, in that it is based on a process of private-sector cost minimisation, rather than a messy political economy process. It is, however, a pity to suspect that monetary economics may be driven more by technical and ideological purity than by empirical and predictive capacity.” Goodhart, C. (1998) “ Two concepts of money: implications for the analysis of optimal currency areas”, European Journal of Political Economy, 14: 407-432, p 425.

“If money is a commodity then money is in short supply and the government can run out of money or money aught still to be a commodity as it once was. If it’s not now, then that means that governments by printing something which isn’t really money, which is counterfeit money, can create inflation.” Steven Hail on the implications of the Metalists (or M-Theory as Goodhart called it) approach, in a lecture for ‘Foundations of Modern Money, Institutions and Markets’

I wrote about the political and ideological implications of the ‘barter led to money’ story in my article, ‘Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) in 67 Bullet Points”. Again, rather than rewrite these points, here is a short excerpt.

“The story is that money originated from people bartering goods and services; an early form of our modern capitalist marketplace. Money came ‘from the people’ to support their market activities, not from the government. This story helps downplay the role of government in the management of the money system. It promotes the idea that money was ‘stolen from the people’ by a central authority by nefarious means. And that governments should leave markets alone to get on with what they are good at.

Unlike neoliberal economics, MMT puts forward the idea that governments were central to the creation of our modern monetary system. So, rather than pushing governments aside, as an impediment to the market working as it should, MMT reveals its central role.

The story of how and why money was ‘invented’ is important, because it can either be used to support the approach taken by orthodox economists (Adam Smith Wealth of Nations Chapter IV, Carl Menger – "On the Origins of Money" (1892), Paul Samuelson – "Economics" (1948)), or it can be used to support the approach taken by MMT advocates.

The former say that money arose spontaneously to ‘lubricate markets, via barter, and, therefore, it belongs to the people operating within those markets’. Thus originally arising from social networks and keeping records of debts and obligations within communities. These records and associated legal framework were kept by central authorities, such as local religious temples and latterly, national governments.

If, as an orthodox economist, you can develop a story that shows ‘money came from the people’, you can argue that the governments role in managing that economy is not wholly legitimate. You may also feel justified in saying that the government is interfering with the workings of the market, preventing it from doing its job as well as it could. I.e. it’s best not to interfere with individuals pursuing their self-interest, in a free market, because that’s the best way to ensure positive outcomes for all concerned.

The orthodox approach says that government spending reduces the availability of both goods, services and money that would otherwise be available for private sector use. Develop that further and you can justifiably say that the government stole the people’s money and spent it wastefully. This story supports the idea that governments should not have a large role in the working of the private sector economy.

It’s no surprise, therefore, that orthodox economics textbooks to this day still tell us that money arose from barter systems. (Reference: Graeber; Stevenson and Wolfers) Moreover, many of the mathematical models used even today still treat markets as if they were barter systems.”

If you’re finding value in these articles, become a paid subscriber. Your support allows me to continue to write, teach and to build a community of like-minded individuals—individuals, like you, who understand that MMT offers an opportunity to change the world for the better. Become a paid subscriber now.

If We Kick the Barter Story into Touch, We Are Kicking the Legs from Under Orthodox Economics

The barter story has been useful to keep around, not only because it supports a particular ideological viewpoint (small government, money belongs to the people and unencumbered markets produce the best outcomes for all) but because, as Goodhart writes, ‘it lends itself to better mathematical formalisation’.

A pure barter system allows orthodox economists to assume as Steven Hail writes, “a general equilibrium model of a barter economy as a basis for what they called ‘real analysis’..” I.e, an entire set of models, assumptions and economics approaches that are built on top of the idea that money originated from the barter system. In these models money is not important, it is mere lubrication of the market for services and goods. It is the market that is important; the self-balancing supply and demand of goods and services. It’s no surprise that orthodox economists are keen to cling on to the ‘myth of barter’ - as hundreds of years of analysis and economic thought depends on it being true.

In Conclusion: Listen to Economist Steven Hail – Barter and the Origins of Money – ‘It Did Not Happen’

I will conclude my examination of the ‘barter led naturally to the origins of money’ story by giving economist Steven Hail the last word.

“While orthodox macroeconomics is a form of real analysis, based on a core model of a barter economy, nothing remotely like that economy has ever existed. It makes no sense to imagine a commodity within this barter system being adopted due to transactions costs, imperfect information or any other inefficiencies which might be imagined within such a barter system. It did not happen and imagining that money evolved out of such a market system under these circumstances leads to a misunderstanding of what money is, and of the significance of money and finance within real-world economies. This is the foundation myth of real analysis as soft economics. It gave us macroeconomic models where an endogenously driven financial crisis was ruled out by definition, in spite of the fact that such crises have been common historical events.” Steven Hail, (2018) Economics for Sustainable Prosperity, p24

That’s all for now. Don’t forget to subscribe to support MMT101DOTORG. Spread the word that a better world is possible.

Links to some of my most popular newsletters

Become a paid subscribers for access to additional content:

A Permanent Home for MMT101 Paid Subscriber Resources – Factsheets, book recommendations, academic papers, MMT podcasts and more.

MMT Factsheet 3: If Taxes Are Not For Spending What Are They For?

Support MMT101.org by Becoming a Paid Subscriber

If you are enjoying these articles and find them a useful part of your Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) education, please support MMT101.ORG—if you can—via small donation. $5 (or the equivalent in your own currency—SubStack uses US dollars) will allow me to continue this work and reach & teach more people. If you can’t do that, consider sharing the articles and podcasts. By subscribing and supporting, not only will you learn how the economy works, but you will also be part of the efforts to change people’s lives for the better. I do not have the power to do that alone, but as an ever-expanding group who understand that there is a better way, we can make a difference.

Thanks,

Jim

A very interesting article. How would you categorise the emergence of spontaneous currencies, such as the well-known use of cigarettes among WWII POWs? Obviously no government involved!

Credit and barter are not mutually exclusive. Commodity money is a thing and it did replace barter, not in domestic markets but in foreign trade. The flaw in the metallist story is it does not make that distinction, in fact it ignores the (usually) prior existence of domestic credit-based money and tries to tack it on as a late degenerate development.

From the earliest times there were attempts to unify the inside (credit) money and the outside (commodity) money. Initially this was done by setting a fixed exchange rate, then by minting gold coins denominated in a unit of account, then by a gold standard. The latest effort--the Euro--ditched the gold and replaced it with rules.

These hybrid monies are tantamount to pegging the exchange rate which causes ructions in the domestic economy and they eventually have to be abandoned--for a while. As you say, there is a deep ideological need to do this so they always try again.