Bare-Bones Guide to Monetary Sovereignty – Some Countries Have It, Others Have Very Little or None

Monetary sovereignty is at the heart of a nation’s economic success or failure. If you want to know why that is the case, this is the article for you.

Sovereignty is about control and it’s about power. In the context of a country, it’s about the power to govern: to make laws; set policies; determine priorities; manage resources and shape relationships with other nations—free from outside interference.

When people hear the word "sovereignty" they tend to think of territorial and political sovereignty—the authority of a nation to govern and defend itself without external constraints or interference. However, sovereignty extends beyond this; it can be, and is, applied to many areas, including, legislative sovereignty, financial sovereignty (currency issuance and taxation), energy sovereignty, food sovereignty, cultural sovereignty and more.

In this article, I focus on monetary sovereignty; specifically, I focus on the idea that monetary sovereignty is at the heart of a nation’s economic success or failure. I demonstrate that monetary sovereignty exists on a spectrum, ranging from countries with full sovereignty to those with little or none.

“Having monetary sovereignty means that a country can prioritise the security and well-being of its people without needing to worry about how to pay for it” Stephanie Kelton (The Deficit Myth, 2020)

What Does Full Monetary Sovereignty Mean?

Full monetary sovereignty implies that a government issues its own currency, collects taxes in that currency and has the power to spend and design policies without interference from outside forces.

Those outside forces could be other countries, financial speculators, foreign lenders or international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

What Are the Minimum Requirements for Full Sovereignty?

The economist Dr Fadhel Kaboub, whose work focuses on the economies of post-colonial countries (for example, Tunisia, Senegal or Egypt), writes that a country cannot have full monetary sovereignty unless it has sovereignty over four key areas:

Financial sovereignty.

Energy sovereignty.

Technology/knowledge sovereignty.

Food sovereignty.

I will take Dr Kaboub’s list as a starting point for this bare-bones guide. I’m calling it a bare-bones guide, because, I will try to avoid the use of too many statistics or an overload of references to support every point I make. My aim is to get the message across in the most direct way possible. If you want more statistics, more examples and more references you will find plenty of them in my article, ‘Currency Issuing Countries Versus Those With Full Monetary Sovereignty’.

This is an overview of what is potentially a complex topic. I explore the areas outlined by Dr Kaboub and I will use my own home country, Scotland, as a case study when exploring issues around energy and food sovereignty.

Ok, let’s get started. The first essential component of full monetary sovereignty is financial sovereignty.

If you’re finding value in these articles, become a paid subscriber. Your support allows me to continue to write, teach and to build a community of like-minded individuals—individuals, like you, who understand that MMT offers an opportunity to change the world for the better. Become a paid subscriber now.

1. Financial Sovereignty

Dr Kaboub points out that to have full financial sovereignty you must have sovereignty over the following areas:

You issue your own currency & collect taxes in that currency.

You have little or no foreign debt.

You have a floating exchange rate.

"...countries like the United States, Japan, Canada, and Australia, among others, enjoy full financial sovereignty, which gives them a wider fiscal policy space to finance domestic job creation, public infrastructure, education, public health, and social services.” Fadhel Kaboub

When it comes to financial sovereignty, countries can be grouped into three broad categories.

Countries with a high degree of financial sovereignty include the United States, the UK, Japan, Canada, and New Zealand. They issue their own currency, tax in that currency, have minimal foreign currency debt and operate under floating exchange rates.

Countries with little or no financial sovereignty often use another country's currency—typically the US dollar. Examples include Ecuador, Zimbabwe, and Panama. These countries tend to have significant foreign currency debt and lack control over monetary policy.

Countries in the middle of the monetary sovereignty spectrum issue their own currency but face constraints due to large foreign currency debts. Many of them peg their currency to the US dollar or a basket of currencies to maintain exchange rate stability, limiting their ability to conduct independent monetary policy. Their reliance on having to earn foreign currency to service debts can mean their focus is moved away from serving the needs of their own citizens.

Why Is Issuing Your Own Currency Important?

Governments such as the UK and the US issue their own currency. This gives them an advantage over countries that do not. It means their finances are not inherently constrained. That’s not to say there are no limits to their spending—spending is limited, first of all by the availability of goods and services to buy in that currency and secondly, by the risk of inflation.

However, for currency-issuing countries like the UK and the US, there are no financial constraints beyond resource availability and inflation. The constraints you hear politicians talk about on your TV (e.g. Rachel Reeves ‘black hole’ in the finances) are in fact self-imposed—often due to beliefs grounded in orthodox economic thinking, such as the need to run ‘balanced budgets’, a set of ‘fiscal rules’ or adherence to a ‘debt ceiling.’ But these are political choices, not technical constraints.

For countries that issue their own currency, all government spending is new money. Politicians decide what to spend, and the central bank ensures those payments are made (by law it is not allowed to refuse). There is never a need to ‘collect’ taxes before spending can occur.

Why Is a Lack of Foreign Debt Important?

Foreign sector debt stifles a country’s ability to make its own policy decisions, often forcing it to prioritise debt repayment over domestic needs. Even countries that issue their own currency are hampered by foreign currency debts: such debts must be repaid in the lender’s currency, which must be earned, borrowed, or generated in some other way.

“There is nothing a nation should avoid as much as borrowing money abroad.” Ulysses Grant to Emperor Meiji, Japan 1879.

As a result, the government focuses on generating foreign currency rather than addressing domestic priorities. For example, farmers may be incentivised to grow strawberries for export rather than staple crops for local consumption because such exports will bring in foreign currency.

This shift means the government is not fully focused on the needs of its own citizens or on addressing the structural weaknesses in its economy: the weaknesses that led to the accumulation of debts in the first place.

For example, a country that needs to import energy or high-value goods such as computers (which require the use of foreign currency reserves) should also focus on investing in increase their renewable energy capability and to educate their citizens. Only a highly educated workforce will have the skills and knowledge required to manufacture the higher-value goods and services that the country needs and currently has to import.

"Prioritising debt payments often means reducing budget allocations for education, health, and critical infrastructure investments. Furthermore, policies that are designed to increase foreign currency earnings to pay off the debt end up being entrapment strategies that deepen the quagmire." Fadhel Kaboub - writing on Tax Justice Network.

Why Is a Floating Exchange Rate Important?

With a floating exchange rate, the value of a country’s currency is determined by supply and demand in the foreign exchange market, rather than being pegged to another currency or commodity. This means the government can freely adjust monetary policy, such as, setting interest rates or controlling inflation without worrying about maintaining a fixed exchange rate. In turn, it enables the government to manage its economy independently, as it is not constrained by the need to defend a pegged currency or hold large reserves of foreign currency to meet obligations.

However, in countries with structural weaknesses in their economies, a free-flowing exchange rate can be dangerous. For example, if their currency weakens, the cost of imports goes up, as does the cost of servicing foreign sector debt. And when the cost of imports go up that means the country is also ‘importing inflation’ - which is destabilising and can lead to business failures. For this reason and others (a stable exchange rate can attract investment) countries with less stable economies often peg their exchange rate to either another currency or a ‘basket of currencies.

Unfortunately, this causes its own problems, as the central bank needs to maintain that peg - and to do that it needs foreign currency reserves. Again this puts pressure on the government to bring in those currency reserves rather than focusing on domestic issues such as health, education and broader issues around domestic economic development.

“MMT indicates that a flexible exchange rate regime maximises the policy space for government to pursue domestic objectives. Once a nation adopts a currency peg of any description (fixed exchange rate, dollarisation, currency board, etc) it loses its full currency sovereignty and compromises domestic policy aspirations." Economist Bill Mitchell

Financial Sovereignty Case Study: Scotland Lacks Financial Sovereignty

Scotland is an unusual case as it is in an ‘equal’ union with England. In theory this means that Scottish MPs are part of the Westminster decision making process. In practice this is not the case; due to the 9 to 1 balance of MPs in favour of England (543 English MPs versus 57 Scottish MPs).

This also means, that in practice, Scotland is a currency user rather than a currency issuer, i.e. it uses the UK Pound. Scotland’s spending is limited by a legal framework setup up by the UK Government.

This lack of financial sovereignty manifests itself in many ways. Here are two examples:

During the 2014 Scottish independence referendum Scots were told by the UK Government that they would ‘not be allowed to use the UK pound’ if it became an independent country: making it clear where the power lay within the UK Parliament. In a truly equal union such a statement would have been impossible as it would have required agreement by Scottish MP’s.

This lack of financial sovereignty was also highlighted during the Covid pandemic - when the devolved Scottish Government wanted to lockdown earlier than the rest of the UK but was unable to because the UK Government would not release the funds to support Scottish businesses.

Scotland was forced to fit in with Westminster’s timetable. If Scotland had been able to act sooner, it would have reduced the initial spread of Covid, lowered peak hospital demand and saved lives. It is estimated that the earlier lockdown would have saved tens of thousands of additional deaths in Scotland.

If you’re finding value in these articles, become a paid subscriber. Your support allows me to continue to write, teach and to build a community of like-minded individuals—individuals, like you, who understand that MMT offers an opportunity to change the world for the better. Become a paid subscriber now.

Case Study: Countries That Use the Euro Have No Financial Sovereignty

Countries that have adopted the Euro gave up their own currencies and, in doing so, surrendered their financial sovereignty. They no longer have control over monetary policy and are subject to spending constraints, including, deficit limits imposed by the European Central Bank (ECB).

Users of the Euro are currency users, not currency issuers. For some countries, this has had serious consequences. For example, during the 2008 downturn, Greece’s economy was effectively devastated by the decisions of the ECB. Austerity measures were imposed, leading to unemployment levels that peaked at approximately 30% overall and over 60% for young people in 2013.

“The Italian Government has to get euros before it can spend them and can potentially become insolvent. There's insolvency risk there if they can't at least guarantee the support of the European Central Bank...But that's not the case with New Zealand's government or the Australian Commonwealth Government because they are currency issuers…” Economist Steven Hail

A Comparison of Countries According to Their Level of Financial Sovereignty

The following table shows the effects of different levels of sovereignty in relation to currency issuance, debt levels and whether or not the country pegs their exchange rate. The three areas outlined by Dr Kaboub as being essential for full financial sovereignty.

Financial Sovereignty - A Spectrum

Download an accessible text version of the above financial sovereignty as a spectrum table.

Financial Sovereignty – Argentina & Ecuador

Download an accessible text version of the above financial sovereignty–Argentina & Ecuador table.

2. Energy Sovereignty

It goes without saying that is impossible to run a country without energy: you need energy to run factories; keep the lights on; power transportation systems and ensure access to basic services like healthcare and education. Without energy and without control of energy a country becomes dependent on external sources, leaving it exposed to supply disruptions and price volatility.

Case Study: Scotland Lacks Energy Sovereignty

Since the 1970s, Scotland’s has had huge oil and gas reserves (Scotland is the largest producer of oil and the second largest producer of gas in Europe). Scotland is also a leader in the production of renewable energy. In 2022 it produced more renewable electricity than it consumed.

‘We live in an energy rich country where we have virtually 100% capacity to generate our renewable electricity and we’re locked into a UK market that prices our electricity based on the wholesale gas price. What an absolute absurdity’. John Swinney MSP Scottish Parliament Debate 7.9.22

However, Scotland, as I mentioned earlier, is in a union with England and energy policy lies with Westminster. Unsurprisingly, and in some sense, quite rightly, the 543 English MPs work in the interest of their own constituencies. Scottish MPs, as a small minority, have little or no impact on the decision making process. Despite an abundance of oil, gas and renewable energy, Scots currently pays some of the highest energy prices in the world.

UK’s energy policies are not designed to work for Scottish citizens. These policies could be changed by the UK Government if the will was there: the will is not there.

Scotland’s lack of sovereignty in this area is also revealed itself in the plans to shut down Scotland's only oil refinery at Grangemouth, which is scheduled to close in the second quarter of 2025. This puts Scotland in the position of producing oil (the cheaper raw resource) but not the high-value refined products from that oil. With the closure of Grangemouth’s refining operations, Scotland will become dependent on imports for refined fuel. This further reduces Scotland’s lack of energy sovereignty.

“The cost of power for industrial businesses has jumped 124 per cent in just five years, according to the Government’s figures, catapulting the UK to the top of international league tables for energy cost. It is now about 50 per cent more expensive than in Germany and France, and four times as expensive as in the US.” Why Scottish businesses are paying the highest energy costs in the world

A Side Note: Scotland Shares Economic and Structural Characteristics with Historical Colonies

Dr Fadhel Kaboub notes that it is in the interests of former colonial powers to use developing countries as sources of cheap labour and raw materials. While Scotland is not comparable to the developing countries Dr Kaboub is referring to—i.e., Scotland is not seen as a source of cheap labour—there are some parallels to be drawn: Scotland’s economy has remained underdeveloped in many areas. On all of the areas essential for monetary sovereignty highlighted by Dr Kaboub, Scotland is arguably has very little or no sovereignty.

For example, since the start of the Union, Scotland’s population has diminished relative to England’s, its port infrastructure has remained largely undeveloped, the Ministry of Defence uses Scotland as the UK's nuclear dumping ground, and since the 1960s, Scotland has hosted a string of US military bases, including nuclear-armed submarines and nuclear mines at Machrihanish on the Mull of Kintyre.

Scotland is used for resource extraction (oil and gas, whisky, renewable energy, and seafood), while much of the high-value processing and profits are concentrated elsewhere, particularly in London and the southeast of England. Financial dependence and limited policy control further reinforce this pattern.

Finance, energy, and retail are dominated by companies headquartered outside Scotland, meaning decision-making and profits are often externalised.

While Scotland has a developed economy, many of its key industries are still structured around serving the UK economy rather than following an independent Scottish economic strategy. For example, Scotland is a net exporter of electricity, but as mentioned earlier, it does not fully control its energy pricing or grid infrastructure.

The Scottish Government operates within a budget largely determined by the UK Treasury, with limited borrowing powers, restricting its fiscal autonomy.

Taken together, these factors suggest that Scotland's economic and political dynamics share similarities with those of a territory lacking full sovereignty. Scotland does not possess complete control over its resources, fiscal policies, or economic direction.

“Most of Scotland’s international shipping operations ended due in part to the lack of investment in the major Scottish central belt ports necessary to cater for modern and larger ships introduced since 'contanerisation’ of world trade. Compared with port infrastructure today in Denmark, Norway, Ireland, Finland, Estonia, Poland etc., Scotland resembles a less developed nation dependent on outdated Victorian port infrastructure.” Baird, Alfred. Doun-Hauden: The Socio-Political Determinants of Scottish Independence (p. 149). (Function).

If you’re finding value in these articles, become a paid subscriber. Your support allows me to continue to write, teach and to build a community of like-minded individuals—individuals, like you, who understand that MMT offers an opportunity to change the world for the better. Become a paid subscriber now.

3. Technology/Knowledge Sovereignty

Technology/knowledge sovereignty refers to a nation's ability to develop, control and access critical technologies, research, and intellectual resources without reliance on foreign powers. This includes domestic innovation, secure digital infrastructure and education systems that foster independent technological advancement. Without it, countries risk dependence on external technology providers, vulnerability to economic and geopolitical pressure and limited capacity for self-sustained development.

Developing advanced, high-value industries requires an educated workforce. An educated workforce requires investment in education and research. If the government is focused on areas such as tourism and export-led growth based on low-wage work and low-value resources, that investment in education can easily be overlooked.

High levels of foreign currency debt are a trap; a trap that is not easy get out of without focusing on solving the structural weaknesses of the economy: those weaknesses include investment in education and research.

4. Food Sovereignty

Governments must ensure their citizens have access to nutritious food—this is a fundamental responsibility of every government.

The Difference Between Food Sovereignty and Food Security

When discussing food sovereignty economists note that there is a difference between food sovereignty and food security.

Food security means ensuring access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food - even if that access means importing that food. However, food sovereignty is about control over structures and policies that govern how food is produced, distributed, and consumed.

In times of crisis, ‘food security’ can evaporate: wars or pandemics or other geopolitical disasters can mean you no longer have access to the food your citizens need. Food sovereignty, on the other hand, means you have the ability to meet your citizens core needs from you own food production.

Food Sovereignty and Local Communities

I should mention that the history of food sovereignty is rooted in local communities rather than in the national sphere. Valerie Segrest, a member of Muckleshoot Indian tribe and native nutrition educator, notes in her TED talk that food sovereignty is a term first coined by a group of peasants farmers called La Vía Campesina in Mons, Belgium. They defined food sovereignty as ‘the right of a community to define it’s own diet and therefore shape its own food system’. They put the focus on small-scale farmers, indigenous practices, and local food production over corporate control and global supply chains. Their aim was to maintain traditional farming knowledge, protect biodiversity and ensure access to nutritious food, free from external pressures such as market fluctuations or trade agreements.

Even as we view food sovereignty at a national level, these aims should still be at the forefront of our thinking: they are essential to the sustainability of our food system at every level.

With that in mind I will finish this article by once again using Scotland as a case study. This time in relation to food sovereignty.

If you’re finding value in these articles, become a paid subscriber. Your support allows me to continue to write, teach and to build a community of like-minded individuals—individuals, like you, who understand that MMT offers an opportunity to change the world for the better. Become a paid subscriber now.

Case Study: Scotland and Food Sovereignty

“Scotland could be food sovereign, it has the resources to be food sovereign, but there are certain obstacles to that happening. The first and most obvious is the concentration of land ownership is so extreme, and that land ownership then distorts the use of land towards Game, Salmon, Deer, Grouse, which as we know is highly inefficient but highly profitable for landed estates. “ Mike Small, Bella Caledonia.

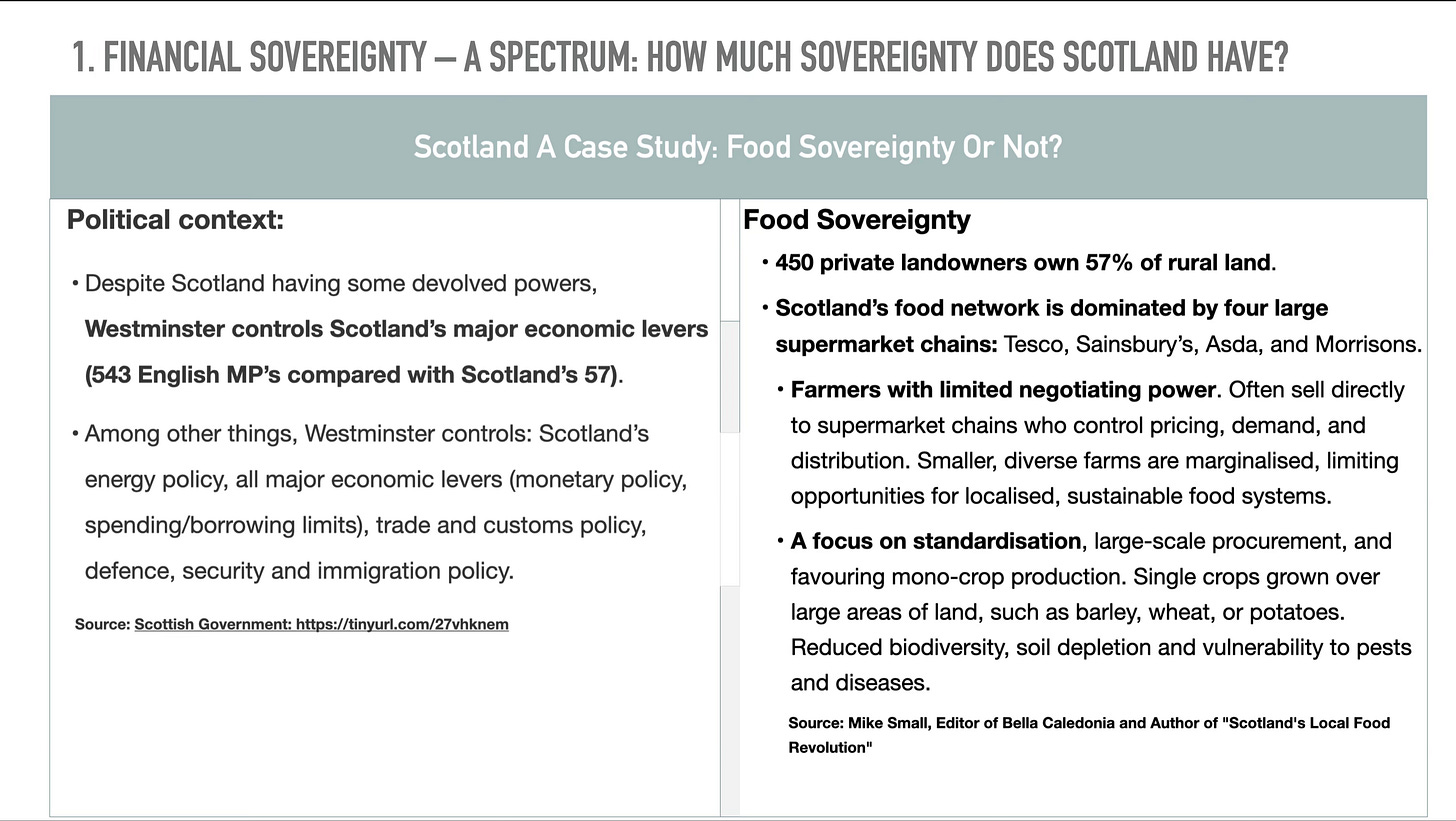

These issues relating to food sovereignty are summarised in the following table. The left-hand column shows that Scotland is rich in food and drink resources: it clearly has an abundance of both. From those statistics you would conclude that Scotland does indeed have food sovereignty. The right-hand column reveals a more complex picture (backed up by the supplementary table). This information reveals that the power over those resources does not necessarily lie with the Scottish Government nor with the local community. Much of the power lies with a small number of landowners and the industrial food complex controlled by a limited number of supermarket chains.

Scotland A Case Study: Food Sovereignty Or Not?

Download an accessible text based version of the above food sovereignty case study, Scotland table.

Download an accessible text based version of the above ‘does Scotland have food sovereignty’ table.

In Conclusion: Monetary Sovereignty Exists on a Spectrum

A country's position on the spectrum of monetary sovereignty determines how much control it has over its economic resources and policies – and its ability to respond to crises. Those with full monetary sovereignty—issuing their own currency, operating a floating exchange rate, and avoiding reliance on foreign debt—have the greatest flexibility. Others, constrained by currency pegs, external debt, or dependence on essential imports, face significant limitations. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for assessing economic policy choices and the degree of true sovereignty a nation possesses.

That’s all for now. Don’t forget to subscribe to support MMT101DOTORG. Spread the word that a better world is possible.

Links to some of my most popular newsletters

Become a paid subscribers for access to additional content:

A Permanent Home for MMT101 Paid Subscriber Resources – Factsheets, book recommendations, academic papers, MMT podcasts and more.

MMT Factsheet 3: If Taxes Are Not For Spending What Are They For?

Support MMT101.org by Becoming a Paid Subscriber

If you are enjoying these articles and find them a useful part of your Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) education, please support MMT101.ORG—if you can—via small donation. $5 (or the equivalent in your own currency—SubStack uses US dollars) will allow me to continue this work and reach & teach more people. If you can’t do that, consider sharing the articles and podcasts. By subscribing and supporting, not only will you learn how the economy works, but you will also be part of the efforts to change people’s lives for the better. I do not have the power to do that alone, but as an ever-expanding group who understand that there is a better way, we can make a difference.

Thanks,

Jim

Excellent explanations of monetary sovereignty. Looking forward to learning more. I am a huge believer in Modern Monetary economics and their descriptions of the actual mechanics of our money system. I get quite worked up about politicians and even educated professionals talking endlessly about how our taxpayer money is being spent and how it is revenue for the federal reserve. I am a fan of Stephanie Kelton, Steve Keen, Randall Wray and all the others in the MMT economic community.

Dear Jim,

Thank you very much for sharing this great article. I wonder, when you talk about external debt, are you only referring to government debt? If external debt is held by private entities, how does that affect a country's monetary sovereignty?

Best regards